See any bugs/typos/confusing explanations? Open a GitHub issue. You can also comment below

★ See also the PDF version of this chapter (better formatting/references) ★

Establishing secure connections over insecure channels

We’ve now compiled all the tools that are needed for the basic goal of cryptography (which is still being subverted quite often) allowing Alice and Bob to exchange messages assuring their integrity and confidentiality over a channel that is observed or controlled by an adversary. Our tools for achieving this goal are:

Public key (aka asymmetric) encryption schemes.

Public key (aka asymmetric) digital signatures schemes.

Private key (aka symmetric) encryption schemes - block ciphers and stream ciphers.

Private key (aka symmetric) message authentication codes and pseudorandom functions.

Hash functions that are used both as ways to compress messages for authentication as well as key derivation and other tasks.

The notions of security we require from these building blocks can vary as well. For encryption schemes we talk about CPA (chosen plaintext attack) and CCA (chosen ciphertext attacks), for hash functions we talk about collision-resistance, being used (combined with keys) as pseudorandom functions, and then sometimes we simply model those as random oracles. Also, all of those tools require access to a source of randomness, and here we use hash functions as well for entropy extraction.

Cryptography’s obsession with adjectives.

As we learn more and more cryptography we see more and more adjectives, every notion seems to have modifiers such as “non-malleable”, “leakage-resilient”, “identity based”, “concurrently secure”, “adaptive”, “non-interactive”, etc. etc. Indeed, this motivated a parody web page of an automatic crypto paper title generator. Unlike algorithms, where typically there are straightforward quantitative tradeoffs (e.g., faster is better), in cryptography there are many qualitative ways protocols can vary based on the assumptions they operate under and the notions of security they provide.

In particular, the following issues arise when considering the task of securely transmitting information between two parties Alice and Bob:

Infrastructure/setup assumptions: What kind of setup can Alice and Bob rely upon? For example in the TLS protocol, typically Alice is a website and Bob is user; using the infrastructure of certificate authorities, Bob has a trusted way to obtain Alice’s public signature key, while Alice doesn’t know anything about Bob. But there are many other variants as well. Alice and Bob could share a (low entropy) password. One of them might have some hardware token, or they might have a secure out of band channel (e.g., text messages) to transmit a short amount of information. There are even variants where the parties authenticate by something they know, with one recent example being the notion of witness encryption (Garg, Gentry, Sahai, and Waters) where one can encrypt information in a “digital time capsule” to be opened by anyone who, for example, finds a proof of the Riemann hypothesis.

Adversary access: What kind of attacks do we need to protect against. The simplest setting is a passive eavesdropping adversary (often called “Eve”) but we sometimes consider an active person-in-the-middle attacks (sometimes called “Mallory”). We sometimes consider notions of graceful recovery. For example, if the adversary manages to hack into one of the parties then it can clearly read their communications from that time onwards, but we would want their past communication to be protected (a notion known as forward secrecy). If we rely on trusted infrastructure such as certificate authorities, we could ask what happens if the adversary breaks into those. Sometimes we rely on the security of several entities or secrets, and we want to consider adversaries that control some but not all of them, a notion known as threshold cryptography. While we typically assume that information is either fully secret or fully public, we sometimes want to model side channel attacks where the adversary can learn partial information about the secret, this is known as leakage-resistant cryptography.

Interaction: Do Alice and Bob get to interact and relay several messages back and forth or is it a “one shot” protocol? You may think that this is merely a question about efficiency but it turns out to be crucial for some applications. Sometimes Alice and Bob might not be two parties separated in space but the same party separated in time. That is, Alice wishes to send a message to her future self by storing an encrypted and authenticated version of it on some media. In this case, absent a time machine, back and forth interaction between the two parties is obviously impossible.

Security goal: The security goals of a protocol are usually stated in the negative- what does it mean for an adversary to win the security game. We typically want the adversary to learn absolutely no information about the secret beyond what she obviously can. For example, if we use a shared password chosen out of \(t\) possibilities, then we might need to allow the adversary \(1/t\) success probability, but we wouldn’t want her to get anything beyond \(1/t+negl(n)\). In some settings, the adversary can obviously completely disconnect the communication channel between Alice and Bob, but we want her to be essentially limited to either dropping communication completely or letting it go by unmolested, and not have the ability to modify communication without detection. Then in some settings, such as in the case of steganography and anonymous routing, we would want the adversary not to find out even the fact that a conversation had taken place.

Basic Key Exchange protocol

The basic primitive for secure communication is a key exchange protocol, whose goal is to have Alice and Bob share a common random secret key \(k\in\{0,1\}^n\). Once this is done, they can use a CCA secure / authenticated private-key encryption to communicate with confidentiality and integrity.

The canonical example of a basic key exchange protocol is the Diffie Hellman protocol. It uses as public parameters a group \(\mathbb{G}\) with generator \(g\), and then follows the following steps:

Alice picks random \(a\leftarrow_R\{0,\ldots,|\mathbb{G}|-1\}\) and sends \(A=g^a\).

Bob picks random \(b\leftarrow_R \{0,\ldots,|\mathbb{G}|-1\}\) and sends \(B=g^b\).

They both set their key as \(k=H(g^{ab})\) (which Alice computes as \(B^a\) and Bob computes as \(A^b\)), where \(H\) is some hash function.

Another variant is using an arbitrary public key encryption scheme such as RSA:

Alice generates keys \((d,e)\) and sends \(e\) to Bob.

Bob picks random \(k \leftarrow_R\{0,1\}^m\) and sends \(E_e(k)\) to Alice.

They both set their key to \(k\) (which Alice computes by decrypting Bob’s ciphertext)

Under plausible assumptions, it can be shown that these protocols are secure against a passive eavesdropping adversary Eve. The notion of security here means that, similar to encryption, if after observing the transcript Eve receives with probability \(1/2\) the value of \(k\) and with probability \(1/2\) a random string \(k'\gets\{0,1\}^n\), then her probability of guessing which is the case would be at most \(1/2+negl(n)\) (where \(n\) can be thought of as \(\log |\mathbb{G}|\) or some other parameter related to the length of bit representation of members in the group).

Authenticated key exchange

The main issue with this key exchange protocol is of course that adversaries often are not passive. In particular, an active Eve could agree on her own key with Alice and Bob separately and then be able to see and modify all future communication. She might also be able to create weird (with some potential security implications) correlations by, say, modifying the message \(A\) to be \(A^2\) etc..

For this reason, in actual applications we typically use authenticated key exchange. The notion of authentication used depends on what we can assume on the setup assumptions. A standard assumption is that Alice has some public keys but Bob doesn’t. The justification for this assumption is that Alice might be a server, which has the capabilities to generate a private/public key pair, disseminate the public key (e.g., using a certificate authority) and maintain the private key in a secure storage. In contrast, if Bob is an individual user, then it might not have access to a secure storage to maintain a private key (since personal devices can often be hacked). Moreover, Alice might not care about Bob’s identity. For example, if Alice is nytimes.com and Bob is a reader, then Bob wants to know that the news he reads really came from the New York Times, but Alice is equally happy to engage in communication with any reader. In other cases, such as gmail.com, after an initial secure connection is setup, Bob can authenticate himself to Alice as a registered user (by sending his login information or sending a “cookie” stored from a past interaction).

It is possible to obtain a secure channel under these assumptions, but one needs to be careful. Indeed, the standard protocol for securing the web: the transport Layer Security (TLS) protocol (and its predecessor SSL) has gone through six revisions (including a name change from SSL to TLS) largely because of security concerns. We now illustrate one of those attacks.

Bleichenbacher’s attack on RSA PKCS V1.5 and SSL V3.0

If you have a public key, a natural approach is to take the encryption-based protocol and simply skip the first step since Bob already knows the public key \(e\) of Alice. This is basically what happened in the SSL V3.0 protocol. However, as was shown by Bleichenbacher in 1998, it turns out this is susceptible to the following attack:

The adversary listens in on a conversation, and in particular observes \(c=E_e(k)\) where \(k\) is the private key.

The adversary then starts many connections with the server with ciphertexts related to \(c\), and observes whether they succeed or fail (and in what way they fail, if they do). It turns out that based on this information, the adversary would be able to recover the key \(k\).

Specifically, the version of RSA (known as PKCS #1 V1.5) used in the SSL V3.0 protocol requires the value \(x\) to have a particular format, with the top two bytes having a certain form. If in the course of the protocol, a server decrypts \(y\) and gets a value \(x\) not of this form then it would send an error message and halt the connection. While the designers of SSL V3.0 might not have thought of it that way, this amounts to saying that an SSL V3.0 server supplies to any party an oracle that on input \(y\) outputs \(1\) iff \(y^{d} \pmod{m}\) has this form, where \(d = e^{-1} \pmod{|\Z^*_m|}\) is the secret decryption key. It turned out that one can use such an oracle to invert the RSA function. For a result of a similar flavor, see the (1/2 page) proof of Theorem 11.31 (page 418) in KL, where they show that an oracle that given \(y\) outputs the least significant bit of \(y^d \pmod{m}\) allows one to invert the RSA function.1

For this reason, new versions of the SSL used a different variant of RSA known as PKCS #1 V2.0 which satisfies (under assumptions) chosen ciphertext security (CCA) and in particular such oracles cannot be used to break the encryption. Nonetheless, there are still some implementation issues that allowed adversaries to perform some attacks, specifically Manger showed that depending on how PKCS #1 V2.0 is implemented, it might be possible to still launch an attack. The main reason is that the specification states several conditions under which decryption box is supposed to return “error”. The proof of CCA security crucially relies on the attacker not being able to distinguish which condition caused the error message. However, some implementations could still leak this information, for example by checking these conditions one by one, and so returning “error” quicker when the earlier conditions hold. See discussion in Katz-Lindell (3rd ed) 12.5.4.

Chosen ciphertext attack security for public key cryptography

The concept of chosen ciphertext attack security makes perfect sense for public key encryption as well. It is defined in the same way as it was in the private key setting:

A public key encryption scheme \((G,E,D)\) is chosen ciphertext attack (CCA) secure if every efficient Mallory wins in the following game with probability at most \(1/2+ negl(n)\):

The keys \((e,d)\) are generated via \(G(1^n)\), and Mallory gets the public encryption key \(e\) and \(1^n\).

For \(poly(n)\) rounds, Mallory gets access to the function \(c \mapsto D_d(c)\). (She doesn’t need access to \(m \mapsto E_e(m)\) since she already knows \(e\).)

Mallory chooses a pair of messages \(\{ m_0,m_1 \}\), a secret \(b\) is chosen at random in \(\{0,1\}\), and Mallory gets \(c^* = E_e(m_b)\). (Note that she of course does not get the randomness used to generate this challenge encryption.)

Mallory now gets another \(poly(n)\) rounds of access to the function \(c \mapsto D_d(c)\) except that she is not allowed to query \(c^*\).

Mallory outputs \(b'\) and wins if \(b'=b\).

In the private key setting, we achieved CCA security by combining a CPA-secure private key encryption scheme with a message authenticating code (MAC), where to CCA-encrypt a message \(m\), we first used the CPA-secure scheme on \(m\) to obtain a ciphertext \(c\), and then added an authentication tag \(\tau\) by signing \(c\) with the MAC. The decryption algorithm first verified the MAC before decrypting the ciphertext. In the public key setting, one might hope that we could repeat the same construction using a CPA-secure public key encryption and replacing the MAC with digital signatures.

Try to think what would be such a construction, and whether there is a fundamental obstacle to combining digital signatures and public key encryption in the same way we combined MACs and private key encryption.

Alas, as you may have realized, there is a fly in this ointment. In a signature scheme (necessarily) it is the signing key that is secret, and the verification key that is public. But in a public key encryption, the encryption key is public, and hence it makes no sense for it to use a secret signing key. (It’s not hard to see that if you reveal the secret signing key then there is no point in using a signature scheme in the first place.)

Why CCA security matters. For the reasons above, constructing CCA secure public key encryption is very challenging. But is it worth the trouble? Do we really need this “ultra conservative” notion of security? The answer is yes. Just as we argued for private key encryption, chosen ciphertext security is the notion that gets us as close as possible to designing encryptions that fit the metaphor of secure sealed envelopes. Digital analogies will never be a perfect imitation of physical ones, but such metaphors are what people have in mind when designing cryptographic protocols, which is a hard enough task even when we don’t have to worry about the ability of an adversary to reach inside a sealed envelope and XOR the contents of the note written there with some arbitrary string. Indeed, several practical attacks, including Bleichenbacher’s attack above, exploited exactly this gap between the physical metaphor and the digital realization. For more on this, please see Victor Shoup’s survey where he also describes the Cramer-Shoup encryption scheme which was the first practical public key system to be shown CCA secure without resorting to the random oracle heuristic. (The first definition of CCA security, as well as the first polynomial-time construction, was given in a seminal 1991 work of Dolev, Dwork and Naor.)

CCA secure public key encryption in the Random Oracle Model

We now show how to convert any CPA-secure public key encryption scheme to a CCA-secure scheme in the random oracle model (this construction is taken from Fujisaki and Okamoto, CRYPTO 99). In the homework, you will see a somewhat simpler direct construction of a CCA secure scheme from a trapdoor permutation, a variant of which is known as OAEP (which has better ciphertext expansion) has been standardized as PKCS #1 V2.0 and is used in several protocols. The advantage of a generic construction is that it can be instantiated not just with the RSA and Rabin schemes, but also directly with Diffie-Hellman and Lattice based schemes (though there are direct and more efficient variants for these as well).

CCA-ROM-ENC Scheme:

Ingredients: A CPA-secure public key encryption scheme \((G',E',D')\) and three hash functions \(H,H',H'':\{0,1\}^*\rightarrow\{0,1\}^n\) (which we model as independent random oracles2).

Notes: We assume that \(E'\) takes \(n\) bit messages (since CPA security is preserved under concatenation, a one-bit scheme can be transformed into such a scheme). Since \(E'\) is (necessarily) randomized, we denote by \(E'(x;s)\) the encryption of the message \(x\) using the randomness \(s\). We assume that the number of bits of randomness \(E'\) uses is \(n\). (Otherwise we can modify the scheme to use \(n\) bits using a pseudorandom generator, or modify the co-domain of \(H\) to be the space of random choices for \(E'\).)

Key generation: We generate keys \((e,d)=G'(1^n)\) for the underlying encryption scheme.

Encryption: To encrypt a message \(m\in\{0,1\}^\ell\), we select \(r \leftarrow_R \{0,1\}^n\), and output

\[E_e(m) = E'_e(r ; H(m\|r)) \| H''(r) \oplus m \| H'(m \| r)\]recall that \(E'_e(r ; s)\) denotes the encryption of the message \(r\) using randomness \(s\).

- Decryption: To decrypt a ciphertext \(c\|y \| h\) first let \(r=D'_d(c)\), then compute \(m=H''(r) \oplus y\). Finally check that \(c= E'_e(r ; H(m\|r))\) and \(h=H'(m\|r)\). If either check fails we output

error; otherwise we output \(m\).

The above CCA-ROM-ENC scheme is CCA secure.

Let \(A\) be a polynomial-time adversary that wins the “CCA Game” with respect to the scheme \((G,E,D)\) with probability \(1/2 + \epsilon\). We will show (Claim 1) that there is an adversary \(\tilde{A}\) that can win in this game with probability \(1/2 + \epsilon - negl(n)\) without using the decryption box. We will then show (Claim 2) that this implies that \(A'\) can win the CPA game with respect to the scheme \((G',E',D')\) with probability \(1/2 + \Omega(\epsilon)\). We start by establishing the first claim:

Claim 1: Under the above assumptions, there exists a polynomial-time adversary \(\tilde{A}\) that wins the CCA game with respect to the scheme \((G,E,D)\) without making any queries to the decryption box.

Proof of Claim 1: The adversary \(\tilde{A}\) will simulate \(A\), keeping track of all of \(A\)’s queries to its decryption and random oracles. Whenever \(A\) makes a query \(c\|y\|h\) to the decryption oracle, then \(\tilde{A}\) will respond to it using the following “fake” decryption box \(\tilde{D}\): check whether \(h\) was returned before from the random oracle \(H'\) as a response to a query \(m\|r\) by \(A\). If this is the case, then \(\tilde{A}\) will check if \(c = E'_e(r;H(m\|r))\) and \(y= H''(r) \oplus m\). If so, then it will return \(m\), otherwise it will return error. Note that \(\tilde{D}(c\|y\|h)\) is computed without any knowledge of the secret key \(d\).

We claim that the probability that \(\tilde{A}\) will return an answer that differs from the true decryption box is negligible. Indeed, for each particular query \(c\|y\|h\), first observe that if \(\tilde{D}(c\|y\|h)\) is not error then \(\tilde{D}(c\|y\|h) = D_d(c\|y\|h)\). Indeed, in this case it holds that \(c=E'_e(m;H(m\|r))\), \(y=H'(r) \oplus m\) and \(h=H'(m\|r)\). Hence this is a properly formatted encryption of \(m\), on which the true decryption box will return \(m\) as well.

So the only way that \(D\) and \(\tilde{D}\) differ is if \(D_d(c\|y\|h)=m\) but \(\tilde{D}(c\|y\|h)\) returns error. For this it must be the case that for \(r=D'_d(c)\), \(h=H'(m\|r)\) but \(m\|r\) was not queried before by \(A\). There are two options: either \(m\|r\) was not queried at all, but then by the “lazy evaluation” paradigm, the value \(H'(m\|r)\) is chosen uniformly in \(\{0,1\}^n\) independently of \(h\), and the probability that it equals \(h\) is \(2^{-n}\). The other option is that \(m\|r\) was queried but not by the adversary. The only other party that can make queries to the oracle in the CCA game is the challenger, and it only makes a single query to \(H'\) when producing the challenge ciphertext \(C^* = c^*\|y^*\|h^*\) with \(h^* = H'(m^*\|r^*)\). Now the adversary is not allowed to make the query \(C^*\) so in this case the query must have the form \(c\|y\|h^*\) where \(c\|y \neq c^*\|y^*\). But the only way that \(D_d(c\|y\|h^*)\) returns a value other than error is if for \(r=D'_d(c)\) and \(m = y \oplus H''(r)\), \(c=E_e(r;H(m\|r))\) and \(h^* = H'(m\|r)\). Since the probability of a collision in \(H'\) is negligible, this can only happen if \(m\|r = m^*\|r^*\), but in this case it will hold that \(c=c^*\) and \(y=y^*\), contradicting the fact that the ciphertext must differ from \(C^*\). QED (Claim 1)

Claim 2: Under the above assumptions, there exists a polynomial-time adversary \(A'\) that wins the CPA game with respect to the scheme \((G',E',D')\) with probability at least \(1/2 + \epsilon/10\).

Proof of Claim 2:

\(A'\) runs the full CCA experiment with the adversary \(\tilde{A}\) obtained from Claim 1, simulating the random oracles \(H,H',H''\) using “lazy evaluation”. When the time comes and the adversary \(\tilde{A}\) chooses two ciphertexts \(m_0,m_1\), then \(A'\) does the following:

The adversary \(A'\) will choose \(r_0,r_1 \leftarrow_R \{0,1\}^n\), give them to its own challenger and get \(c^*\) which is either an encryption of \(r_{b^*}\) under \(E'_e\) for \(b^* \leftarrow_R \{0,1\}\). If the adversary \(\tilde{A}\) made in the past a query of the form \(r_b\) or \(m_b\|r_{b'}\) for \(b,b' \in \{0,1\}\) to one of the random oracles then we stop the experiment and declare failure. (Since \(r_0,r_1\) are random in \(\{0,1\}^n\) and \(\tilde{A}\) made only polynomially many queries, the probability of this happening is negligible).

The adversary \(A'\) will now give \(c^* \| y^* \| h^*\) with \(y^*,h^* \leftarrow_R \{0,1\}^n\) to \(\tilde{A}\) as the response to the challenge. (Note that this ciphertext does not involve neither \(m_0\) nor \(m_1\) in any way.)

Now if the adversary \(\tilde{A}\) makes a query of the form \(r_b\) or \(m\|r_b\) for \(b\in \{0,1\}\) to one of its oracles, then \(A'\) will output \(b\). Otherwise, it outputs a random output.

Note that the adversary \(A'\) ignores the output of \(\tilde{A}\). It only cares about the queries that \(\tilde{A}\) makes. Let’s say that an “\(r_b\) query is one that has \(r_b\) as a postfix”. To finish the proof we make the following two claims:

Claim 2.1: The probability that \(\tilde{A}\) makes an \(r_{1-b^*}\) query is negligible. Proof: This is because the only value that \(\tilde{A}\) receives that depends on one of \(r_0,r_1\) is \(c^*\) which is an encryption of \(r_{b^*}\). Hence \(\tilde{A}\) never sees any value that depends on \(r_{1-b^*}\) and since it is uniform in \(\{0,1\}^n\), the probability that \(\tilde{A}\) makes a query with this postfix is negligible. QED (Claim 2.1)

Claim 2.2: \(\tilde{A}\) will make an \(r_{b^*}\) query with probability at least \(\epsilon/2\). Proof: Let \(c^* = E'_e(r_{b^*} ; s^*)\) where \(s^*\) is the randomness used in producing it. By the lazy evaluation paradigm, since no \(r_{b^*}\) query was made up to that point, the distribution would be identical if we defined \(H(m_b\|r_{b^*})=s^*\), defined \(H''(r_{b^*}) = y^* \oplus m_b\) and define \(h^* = H'(m_b\|r_{b^*})\). Hence the distribution of the ciphertext is identical to how it is distributed in the actual CCA game. Now, since \(\tilde{A}\) wins the CCA game with probability \(1/2 + \epsilon - negl(n)\), in this game it must query \(H''\) at \(r_{b^*}\) with probability at least \(\epsilon/2\). Indeed, conditioned on not querying \(H''\) at this value, the string \(y^*\) is independent of the message \(m_0\), and the adversary cannot win the game with probability more than \(1/2\). QED (Claim 2.2)

Together Claims 2.1 and 2.2 imply that the adversary \(\tilde{A}\) makes an \(r_{b^*}\) query with probability at least \(\epsilon/2\), and makes an \(r_{1-b^*}\) query with negligible probability, hence our adversary \(A'\) will output \(b^*\) with probability at least \(\epsilon/2\), and with all but a negligible part of the remaining probability will guess randomly, leading to an overall success in the CPA game of at least \(1/2 + \epsilon/2\). QED (Claim 2 and hence theorem)

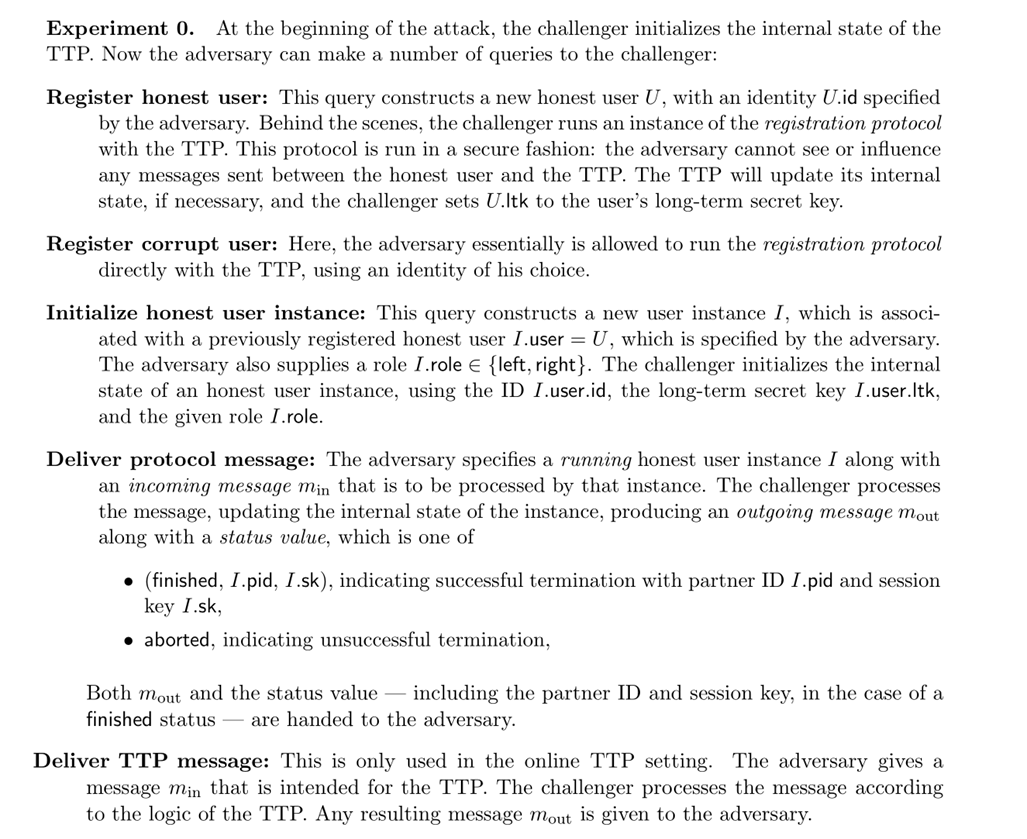

Defining secure authenticated key exchange

The basic goal of secure communication is to set up a secure channel between two parties Alice and Bob. We want to do so over an open network, where messages between Alice and Bob might be read, modified, deleted, or added by the adversary. Moreover, we want Alice and Bob to be sure that they are talking to one another rather than other parties. This raises the question of what is identity and how is it verified. Ultimately, if we want to use identities, then we need to trust some authority that decides which party has which identity. This is typically done via a certificate authority (CA). This is some trusted authority, whose verification key \(v_{CA}\) is public and known to all parties. Alice proves in some way to the CA that she is indeed Alice, and then generates a pair \((s_{Alice},v_{Alice})\), and gets from the CA the message \(\sigma_{Alice}\)=“The key \(v_{Alice}\) belongs to Alice” signed with \(s_{CA}\).3 Now Alice can send \((v_{Alice},\sigma_{Alice})\) to Bob to certify that the owner of this public key is indeed Alice.

For example, in the web setting, certain certificate authorities can certify that a certain public key is associated with a certain website. If you go to a website using the https protocol, you should see a “lock” symbol on your browser which will give you details on the certificate. Often the certificate is a chain of certificate. If I click on this lock symbol in my Chrome browser, I see that the certificate that amazon.com’s public key is some particular string (corresponding to a 2048 RSA modulos and exponent) is signed by the Symantec Certificate authority, whose own key is certified by Verisign. My communication with Amazon is an example of a setting of one sided authentication. It is important for me to know that I am truly talking to amazon.com, while Amazon is willing to talk to any client. (Though of course once we establish a secure channel, I could use it to login to my Amazon account.) Chapter 21 of Boneh Shoup contains an in depth discussion of authenticated key exchange protocols, see for example ?? ??. Because the definition is so involved, we will not go over the full formal definitions in this book, but I recommend Boneh-Shoup for an in-depth treatment.

the definitions of protocols AEK1 - AEK4.

the definitions of protocols AEK1 - AEK4.

The compiler approach for authenticated key exchange

There is a generic “compiler” approach to obtaining authenticated key exchange protocols:

Start with a protocol such as the basic Diffie-Hellman protocol that is only secure with respect to a passive eavesdropping adversary.

Then compile it into a protocol that is secure with respect to an active adversary using authentication tools such as digital signatures, message authentication codes, etc., depending on what kind of setup you can assume and what properties you want to achieve.

This approach has the advantage of being modular in both the construction and the analysis. However, direct constructions might be more efficient. There are a great many potentially desirable properties of key exchange protocols, and different protocols achieve different subsets of these properties at different costs. The most common variant of authenticated key exchange protocols is to use some version of the Diffie-Hellman key exchange. If both parties have public signature keys, then they can simply sign their messages and then that effectively rules out an active attack, reducing active security to passive security (though one needs to include identities in the signatures to ensure non repeating of messages, see here).

The most efficient variants of Diffie Hellman achieve authentication implicitly, where the basic protocol remains the same (sending \(X=g^x\) and \(Y=g^y\)) but the computation of the secret shared key involves some authentication information. Of these protocols a particularly efficient variant is the MQV protocol of Law, Menezes, Qu, Solinas and Vanstone (which is based on similar principles as DSA signatures), and its variant HMQV by Krawczyk that has some improved security properties and analysis.

Password authenticated key exchange.

NOTE: The following three parts are not yet written - we will discuss them in class, but please at least skim the resources pointed out below

PAKE is covered in Boneh-Shoup Chapter 21.11

Client to client key exchange for secure text messaging - ZRTP, OTR, TextSecure

To be completed. See Matthew Green’s blog , text secure, OTR.

Security requirements: forward secrecy, deniability.

Heartbleed and logjam attacks

Vestiges of past crypto policies.

Importance of “perfect forward secrecy”

- ↩

The first attack of this flavor was given in the 1982 paper of Goldwasser, Micali, and Tong. Interestingly, this notion of “hardcore bits” has been used for both practical attacks against cryptosystems as well as theoretical (and sometimes practical) constructions of other cryptosystems.

- ↩

Recall that it’s easy to obtain two independent random oracles \(H,H'\) from a single oracle \(H''\), for example by letting \(H(x)=H''(0\|x)\) and \(H'(x)=H''(1\|x)\). Similarly we can extend this to three, four or any number of oracles.

- ↩

The registration process could be more subtle than that, and for example Alice might need to prove to the CA that she does indeed know the corresponding secret key.

Comments

Comments are posted on the GitHub repository using the utteranc.es app. A GitHub login is required to comment. If you don't want to authorize the app to post on your behalf, you can also comment directly on the GitHub issue for this page.

Compiled on 11/17/2021 22:36:31

Copyright 2021, Boaz Barak.

This work is

licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Produced using pandoc and panflute with templates derived from gitbook and bookdown.