See any bugs/typos/confusing explanations? Open a GitHub issue. You can also comment below

★ See also the PDF version of this chapter (better formatting/references) ★

Chosen Ciphertext Security

Short recap

Let’s start by reviewing what we have learned so far:

We can mathematically define security for encryption schemes. A natural definition is perfect secrecy: no matter what Eve does, she can’t learn anything about the plaintext that she didn’t know before. Unfortunately this requires the key to be as long as the message, thus placing a severe limitation on the usability of it.

To get around this, we need to consider computational considerations. A basic object is a pseudorandom generator and we considered the PRG Conjecture which stipulates the existence of an efficiently computable function \(G:\{0,1\}^n\rightarrow\{0,1\}^{n+1}\) such that \(G(U_n)\approx U_{n+1}\) (where \(U_m\) denotes the uniform distribution on \(\{0,1\}^m\) and \(\approx\) denotes computational indistinguishability).1

We showed that the PRG conjecture implies a pseudorandom generator of any polynomial output length which in particular via the stream cipher construction implies a computationally secure encryption with plaintext arbitrarily larger than the key. (The only restriction is that the plaintext is of polynomial size which is needed anyway if we want to actually be able to read and write it.)

We then showed that the PRG conjecture actually implies a stronger object known as a pseudorandom function (PRF) function collection: this is a collection \(\{ f_s \}\) of functions such that if we choose \(s\) at random and fix it, and give an adversary a black box computing \(i \mapsto f_s(i)\) then she can’t tell the difference between this and a blackbox computing a random function.2

Pseudorandom functions turn out to be useful for identification protocols, message authentication codes and this strong notion of security of encryption known as chosen plaintext attack (CPA) security where we are allowed to encrypt many messages of Eve’s choice and still require that the next message hides all information except for what Eve already knew before.

Going beyond CPA

It may seem that we have finally nailed down the security definition for encryption. After all, what could be stronger than allowing Eve unfettered access to the encryption function? Clearly an encryption satisfying this property will hide the contents of the message in all practical circumstances. Or will it?

Please stop and play an ominous sound track at this point.

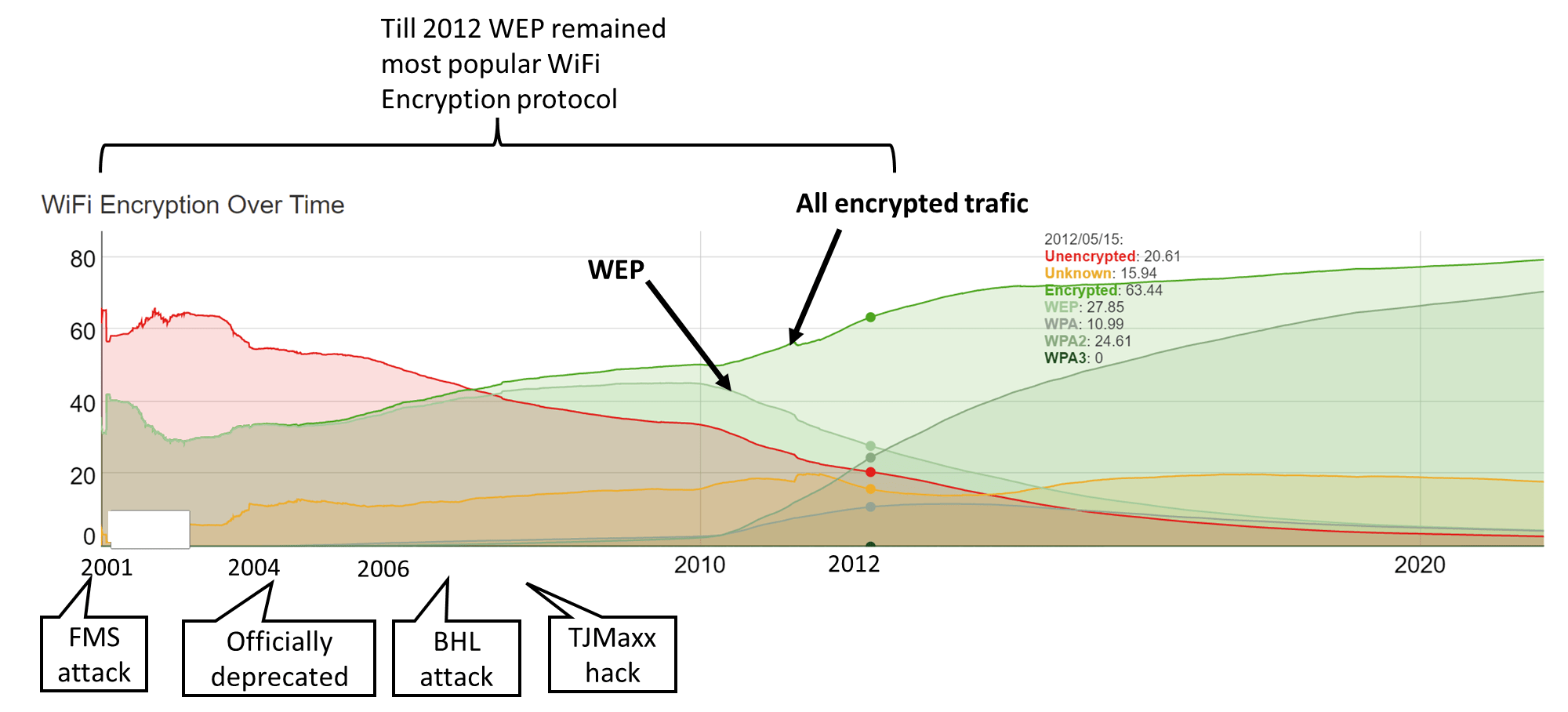

Example: The Wired Equivalence Privacy (WEP)

The Wired Equivalence Privacy (WEP) protocol is perhaps one of the most inaccurately named protocols of all times. It was invented in 1999 for the purpose of securing Wi-Fi networks so that they would have virtually the same level of security as wired networks, but already early on several security flaws were pointed out. In particular in 2001, Fluhrer, Mantin, and Shamir showed how the RC4 flaws we mentioned in prior lecture can be used to completely break WEP in less than one minute. Yet, the protocol lingered on and for many years after was still the most widely used WiFi encryption protocol as many routers had it as the default option. In 2007 the WEP was blamed for a hack stealing 45 million credit card numbers from T.J. Maxx. In 2012 (after 11 years of attacks!) it was estimated that it is still used in about a quarter of encrypted wireless networks, and in 2014 it was still the default option on many Verizon home routers. It is still (!) used in some routers, see Figure 6.1. This is a great example of how hard it is to remove insecure protocols from practical usage (and so how important it is to get these protocols right).

Here we will talk about a different flaw of WEP that is in fact shared by many other protocols, including the first versions of the secure socket layer (SSL) protocol that is used to protect all encrypted web traffic.

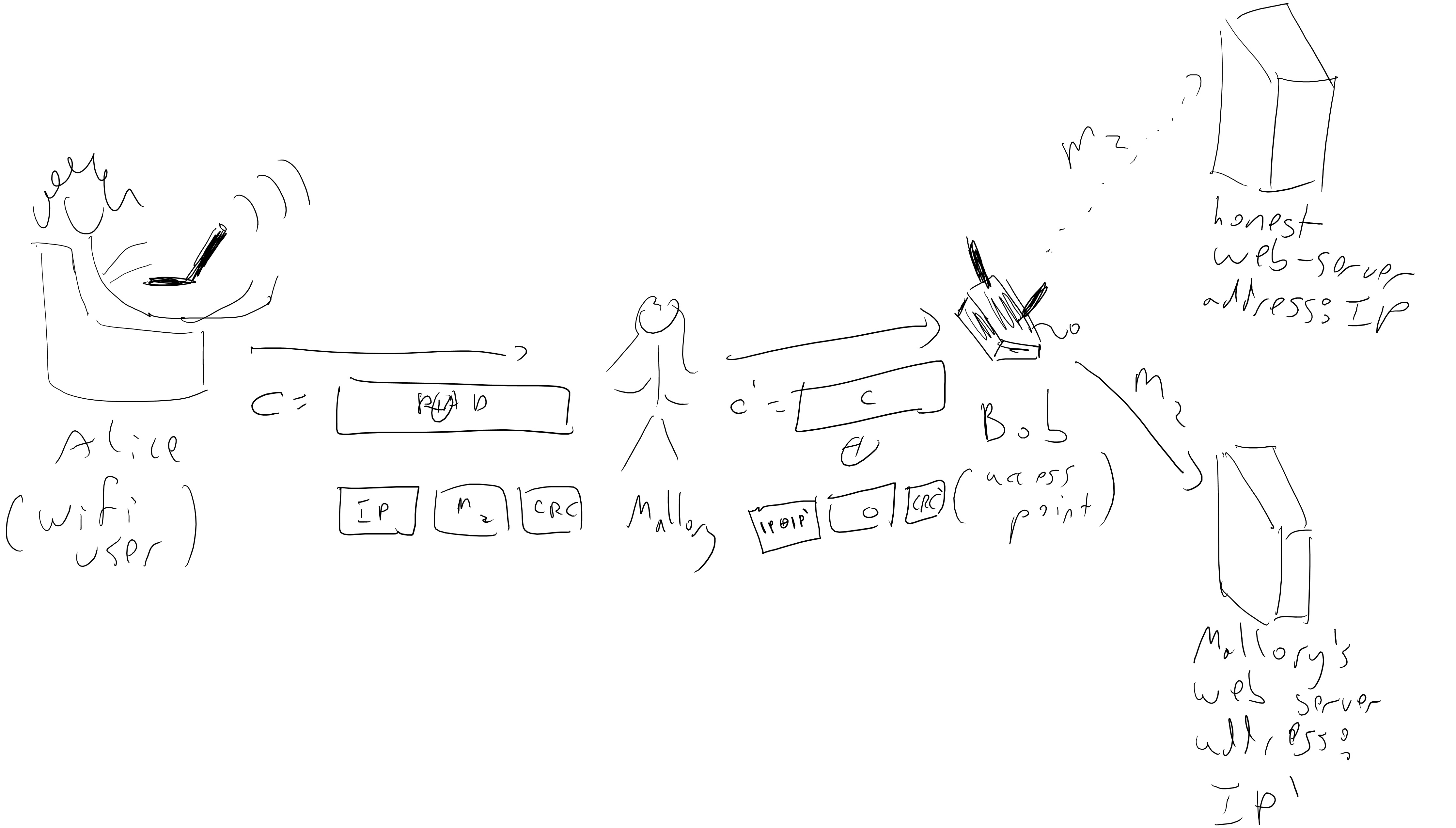

To avoid superfluous details we will consider a highly abstract (and somewhat inaccurate) version of WEP that still demonstrates our main point. In this protocol Alice (the user) sends to Bob (the access point) an IP packet that she wants routed somewhere on the internet.

Thus we can think of the message Alice sends to Bob as a string \(m\in\{0,1\}^\ell\) of the form \(m=m_1\|m_2\) where \(m_1\) is the IP address this packet needs to be routed to and \(m_2\) is the actual message that needs to be delivered. In the WEP protocol, the message that Alice sends to Bob has the form \(E_k(m\|\ensuremath{\mathit{CRC}}(m))\) (where \(\|\) denotes concatenation and \(\ensuremath{\mathit{CRC}}(m)\) is some cyclic redundancy check). A \(\ensuremath{\mathit{CRC}}\) is some function mapping \(\{0,1\}^n\) to \(\{0,1\}^t\) which is meant to enable detection of errors in typing or communication. The idea is that if a message \(m\) is mistyped into \(m'\), then it is very likely that \(\ensuremath{\mathit{CRC}}(m) \neq \ensuremath{\mathit{CRC}}(m')\). It is similar to the checksum digits used in credit card numbers and many other cases. Unlike a message authentication code, a CRC does not have a secret key and is not secure against adversarial perturbations.

The actual encryption WEP used was RC4, but for us it doesn’t really matter. What does matter is that the encryption has the form \(E_k(m') = pad \oplus m'\) where \(pad\) is computed as some function of the key. In particular the attack we will describe works even if we use our stronger CPA secure PRF-based scheme where \(pad=f_k(r)\) for some random (or counter) \(r\) that is sent out separately.

Now the security of the encryption means that an adversary seeing the ciphertext \(c=E_k(m\|\ensuremath{\mathit{CRC}}(m))\) will not be able to know \(m\), but since this is traveling over the air, the adversary could “spoof” the signal and send a different ciphertext \(c'\) to Bob. In particular, if the adversary knows the IP address \(m_1\) that Alice was using (e.g., for example, the adversary can guess that Alice is probably one of the billions of people that visit the website boazbarak.org on a regular basis) then she can XOR the ciphertext with a string of her choosing and hence convert the ciphertext \(c = pad \oplus (m_1\| m_2 \|\ensuremath{\mathit{CRC}}(m_1,m_2))\) into the ciphertext \(c' = c \oplus x\) where \(x = x_1\|x_2\|x_3\) is computed so that \(x_1 \oplus m_1\) is equal to the adversary’s own IP address!

So, the adversary doesn’t need to decrypt the message- by spoofing the ciphertext she can ensure that Bob (who is an access point, and whose job is to decrypt and then deliver packets) simply delivers it unencrypted straight into her hands. One issue is that Eve modifies \(m_1\) then it is unlikely that the CRC code will still check out, and hence Bob would reject the packet. However, CRC 32 - the CRC algorithm used by WEP - is linear modulo \(2\), that is \(\ensuremath{\mathit{CRC}}(x \oplus x') = \ensuremath{\mathit{CRC}}(x)\oplus \ensuremath{\mathit{CRC}}(x')\). This means that if the original ciphertext \(c\) was an encryption of the message \(m= m_1 \| m_2 \| \ensuremath{\mathit{CRC}}(m_1,m_2)\) then \(c'=c \oplus (x_1\|0^t\|\ensuremath{\mathit{CRC}}(x_1\|0^t))\) will be an encryption of the message \(m'=(m_1 \oplus x_1) \|m_2 \| \ensuremath{\mathit{CRC}}( (x_1\oplus m_1) \| m_2)\) (where \(0^t\) denotes a string of zeroes of the same length \(t\) as \(m_2\), and hence \(m_2 \oplus 0^t = m_2\)). Therefore by XOR’ing \(c\) with \(x_1 \|0^t \| \ensuremath{\mathit{CRC}}(x_1\|0^t)\), the adversary Mallory can ensure that Bob will deliver the message \(m_2\) to the IP address \(m_1 \oplus x_1\) of her choice (see Figure 6.2).

Chosen ciphertext security

This is not an isolated example but in fact an instance of a general pattern of many breaks in practical protocols. Some examples of protocols broken through similar means include XML encryption, IPSec (see also here) as well as JavaServer Faces, Ruby on Rails, ASP.NET, and the Steam gaming client (see the Wikipedia page on Padding Oracle Attacks).

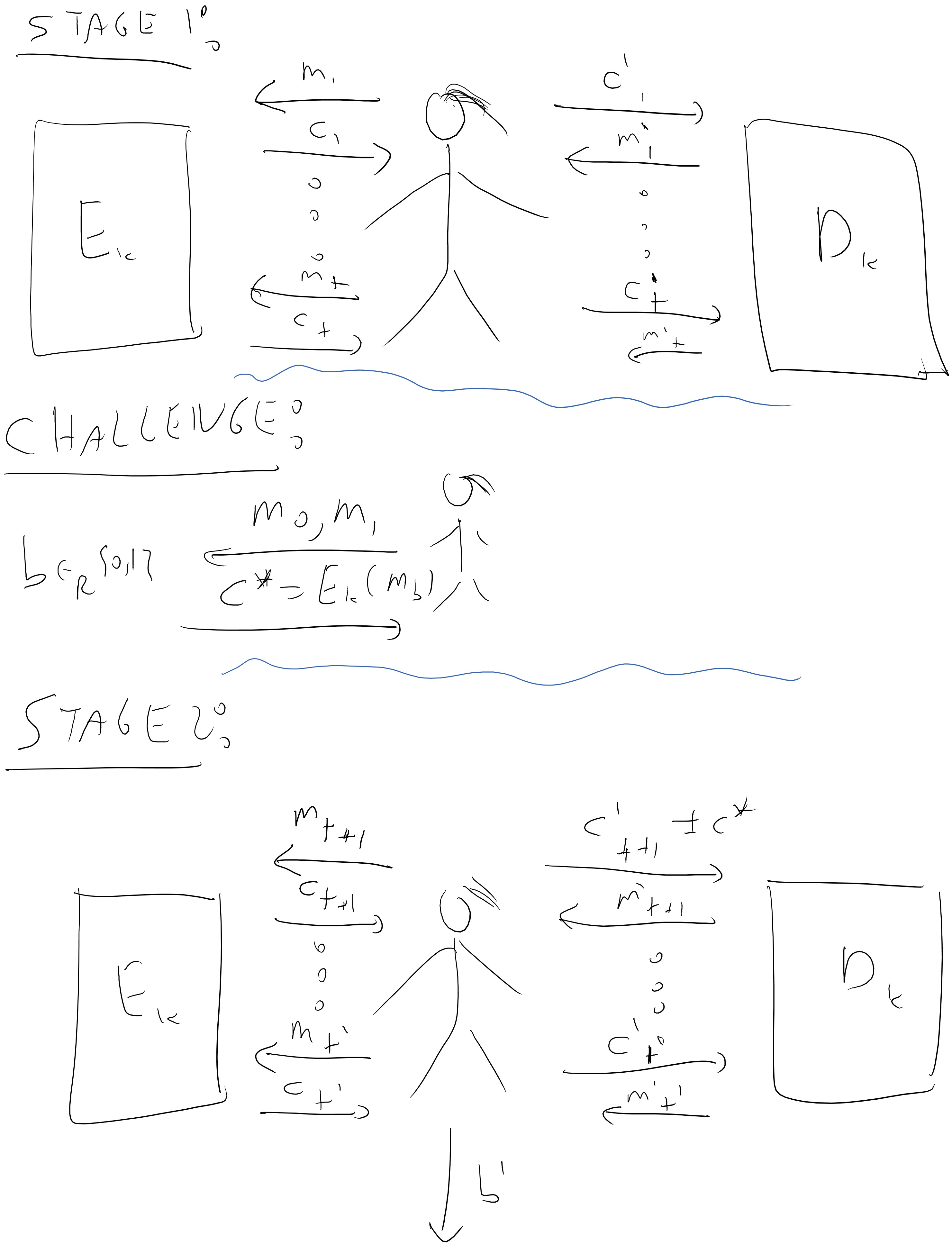

The point is that often our adversaries can be active and modify the communication between sender and receiver, which in effect gives them access not just to choose plaintexts of their choice to encrypt but even to have some impact on the ciphertexts that are decrypted. This motivates the following notion of security (see also Figure 6.3):

An encryption scheme \((E,D)\) is chosen ciphertext attack (CCA) secure if every efficient adversary Mallory wins in the following game with probability at most \(1/2+ negl(n)\):

Mallory gets \(1^n\) where \(n\) is the length of the key

For \(poly(n)\) rounds, Mallory gets access to the functions \(m \mapsto E_k(m)\) and \(c \mapsto D_k(c)\).

Mallory chooses a pair of messages \(\{ m_0,m_1 \}\), a secret \(b\) is chosen at random in \(\{0,1\}\), and Mallory gets \(c^* = E_k(m_b)\).

Mallory now gets another \(poly(n)\) rounds of access to the functions \(m \mapsto E_k(m)\) and \(c \mapsto D_k(c)\) except that she is not allowed to query \(c^*\) to her second oracle.

Mallory outputs \(b'\) and wins if \(b'=b\).

This might seems a rather strange definition so let’s try to digest it slowly. Most people, once they understand what the definition says, don’t like it that much. There are two natural objections to it:

- This definition seems to be too strong: There is no way we would let Mallory play with a decryption box - that basically amounts to letting her break the encryption scheme. Sure, she could have some impact on the ciphertexts that Bob decrypts and observe some resulting side effects, but there is a long way from that to giving her oracle access to the decryption algorithm.

The response to this is that it is very hard to model what is the “realistic” information Mallory might get about the ciphertexts she might cause Bob to decrypt. The goal of a security definition is not to capture exactly the attack scenarios that occur in real life but rather to be sufficiently conservative so that these real life attacks could be modeled in our game. Therefore, having a too strong definition is not a bad thing (as long as it can be achieved!). The WEP example shows that the definition does capture a practical issue in security and similar attacks on practical protocols have been shown time and again (see for example the discussion of “padding attacks” in Section 3.7.2 of the Katz Lindell book.)

- This definition seems to be too weak: What justification do we have for not allowing Mallory to make the query \(c^*\) to the decryption box? After all she is an adversary so she could do whatever she wants. The answer is that the definition would be clearly impossible to achieve if Mallory could simply get the decryption of \(c^*\) and learn whether it was an encryption of \(m_0\) or \(m_1\). So this restriction is the absolutely minimal one we could make without causing the notion to be obviously impossible. Perhaps surprisingly, it turns out that once we make this minimal restriction, we can in fact construct CCA-secure encryptions.

What does CCA have to do with WEP? The CCA security game is somewhat strange, and it might not be immediately clear whether it has anything to do with the attack we described on the WEP protocol. However, it turns out that using a CCA secure encryption would have prevented that attack. The key is the following claim:

Suppose that \((E,D)\) is a CCA secure encryption. Then, there is no efficient algorithm that given an encryption \(c\) of the plaintext \((m_1,m_2)\) outputs a ciphertext \(c'\) that decrypts to \((m'_1,m_2)\) where \(m'_1\neq m_1\).

In particular Lemma 6.2 rules out the attack of transforming \(c\) that encrypts a message starting with a some address \(\ensuremath{\mathit{IP}}\) to a ciphertext that starts with a different address \(\ensuremath{\mathit{IP}}'\). Let us now sketch its proof.

We’ll show that such if we had an adversary \(M'\) that violates the conclusion of the claim, then there is an adversary \(M\) that can win in the CCA game.

The proof is simple and relies on the crucial fact that the CCA game allows \(M\) to query the decryption box on any ciphertext of her choice, as long as it’s not exactly identical to the challenge cipertext \(c^*\). In particular, if \(M'\) is able to morph an encryption \(c\) of \(m\) to some encryption \(c'\) of some different \(m'\) that agrees with \(m\) on some set of bits, then \(M\) can do the following: in the security game, use \(m_0\) to be some random message and \(m_1\) to be this plaintext \(m\). Then, when receiving \(c^*\), apply \(M'\) to it to obtain a ciphertext \(c'\) (note that if the plaintext differs then the ciphertext must differ also; can you see why?) ask the decryption box to decrypt it and output \(1\) if the resulting message agrees with \(m\) in the corresponding set of bits (otherwise output a random bit). If \(M'\) was successful with probability \(\epsilon\), then \(M\) would win in the CCA game with probability at least \(1/2 + \epsilon/10\) or so.

The proof above is rather sketchy. However it is not very difficult and proving Lemma 6.2 on your own is an excellent way to ensure familiarity with the definition of CCA security.

Constructing CCA secure encryption

The definition of CCA seems extremely strong, so perhaps it is not surprising that it is useful, but can we actually construct it? The WEP attack shows that the CPA secure encryption we saw before (i.e., \(E_k(m)=(r,f_k(r)\oplus m)\)) is not CCA secure. We will see other examples of non CCA secure encryptions in the exercises. So, how do we construct such a scheme? The WEP attack actually already hints of the crux of CCA security. We want to ensure that Mallory is not able to modify the challenge ciphertext \(c^*\) to some related \(c'\). Another way to say it is that we need to ensure the integrity of messages to achieve their confidentiality if we want to handle active adversaries that might modify messages on the channel. Since in a great many practical scenarios, an adversary might be able to do so, this is an important message that deserves to be repeated:

To ensure confidentiality, you need integrity.

This is a lesson that has been time and again been shown and many protocols have been broken due to the mistaken belief that if we only care about secrecy, it is enough to use only encryption (and one that is only CPA secure) and there is no need for authentication. Matthew Green writes this more provocatively as

Nearly all of the symmetric encryption modes you learned about in school, textbooks, and Wikipedia are (potentially) insecure.3

exactly because these basic modes only ensure security for passive eavesdropping adversaries and do not ensure chosen ciphertext security which is the “gold standard” for online applications. (For symmetric encryption people often use the name “authenticated encryption” in practice rather than CCA security; those are not identical but are extremely related notions.)

All of this suggests that Message Authentication Codes might help us get CCA security. This turns out to be the case. But one needs to take some care exactly how to use MAC’s to get CCA security. At this point, you might want to stop and think how you would do this…

You should stop here and try to think how you would implement a CCA secure encryption by combining MAC’s with a CPA secure encryption.

If you didn’t stop before, then you should really stop and think now.

OK, so now that you had a chance to think about this on your own, we will describe one way that works to achieve CCA security from MACs. We will explore other approaches that may or may not work in the exercises.

Let \((E,D)\) be CPA-secure encryption scheme and \((S,V)\) be a CMA-secure MAC with \(n\) bit keys and a canonical verification algorithm.4 Then the following encryption \((E',D')\) with keys \(2n\) bits is CCA secure:

\(E'_{k_1,k_2}(m)\) is obtained by computing \(c=E_{k_1}(m)\) , \(\sigma = S_{k_2}(c)\) and outputting \((c,\sigma)\).

\(D'_{k_1,k_2}(c,\sigma)\) outputs nothing (e.g., an error message) if \(V_{k_2}(c,\sigma)\neq 1\), and otherwise outputs \(D_{k_1}(c)\).

Suppose, for the sake of contradiction, that there exists an adversary \(M'\) that wins the CCA game for the scheme \((E',D')\) with probability at least \(1/2+\epsilon\). We consider the following two cases:

Case I: With probability at least \(\epsilon/10\), at some point during the CCA game, \(M'\) sends to its decryption box a ciphertext \((c,\sigma)\) that is not identical to one of the ciphertexts it previously obtained from its encryption box, and obtains from it a non-error response.

Case II: The event above happens with probability smaller than \(\epsilon/10\).

We will derive a contradiction in either case. In the first case, we will use \(M'\) to obtain an adversary that breaks the MAC \((S,V)\), while in the second case, we will use \(M'\) to obtain an adversary that breaks the CPA-security of \((E,D)\).

Let’s start with Case I: When this case holds, we will build an adversary \(F\) (for “forger”) for the MAC \((S,V)\), we can assume the adversary \(F\) has access to the both signing and verification algorithms as black boxes for some unknown key \(k_2\) that is chosen at random and fixed.5 \(F\) will choose \(k_1\) on its own, and will also choose at random a number \(i_0\) from \(1\) to \(T\), where \(T\) is the total number of queries that \(M'\) makes to the decryption box. \(F\) will run the entire CCA game with \(M'\), using \(k_1\) and its access to the black boxes to execute the decryption and decryption boxes, all the way until just before \(M'\) makes the \(i_0^{th}\) query \((c,\sigma)\) to its decryption box. At that point, \(F\) will output \((c,\sigma)\). We claim that with probability at least \(\epsilon/(10T)\), our forger will succeed in the CMA game in the sense that (i) the query \((c,\sigma)\) will pass verification, and (ii) the message \(c\) was not previously queried before to the signing oracle.

Indeed, because we are in Case I, with probability \(\epsilon/10\), in this game some query that \(M'\) makes will be one that was not asked before and hence was not queried by \(F\) to its signing oracle, and moreover, the returned message is not an error message, and hence the signature passes verification. Since \(i_0\) is random, with probability \(\epsilon/(10T)\) this query will be at the \(i_0^{th}\) round. Let us assume that this above event \(\ensuremath{\mathit{GOOD}}\) happened in which the \(i_0\)-th query to the decryption box is a pair \((c,\sigma)\) that both passes verification and the pair \((c,\sigma)\) was not returned before by the encryption oracle. Since we pass (canonical) verification, we know that \(\sigma=S_{k_2}(c)\), and because all encryption queries return pairs of the form \((c',S_{k_2}(c'))\), this means that no such query returned \(c\) as its first element either. In other words, when the event \(\ensuremath{\mathit{GOOD}}\) happens the \(i_0^{th}\) query contains a pair \((c,\sigma)\) such that \(c\) was not queried before to the signature box, but \((c,\sigma)\) passes verification. This is the definition of breaking \((S,V)\) in a chosen message attack, and hence we obtain a contradiction to the CMA security of \((S,V)\).

Now for Case II: In this case, we will build an adversary \(Eve\) for CPA-game in the original scheme \((E,D)\). As you might expect, the adversary \(Eve\) will choose by herself the key \(k_2\) for the MAC scheme, and attempt to play the CCA security game with \(M'\). When \(M'\) makes encryption queries this should not be a problem- \(Eve\) can forward the plaintext \(m\) to its encryption oracle to get \(c=E_{k_1}(m)\) and then compute \(\sigma = S_{k_2}(c)\) since she knows the signing key \(k_2\).

However, what does \(Eve\) do when \(M'\) makes decryption queries? That is, suppose that \(M'\) sends a query of the form \((c,\sigma)\) to its decryption box. To simulate the algorithm \(D'\), \(Eve\) will need access to a decryption box for \(D\), but she doesn’t get such a box in the CPA game (This is a subtle point- please pause here and reflect on it until you are sure you understand it!)

To handle this issue \(Eve\) will follow the common approach of “winging it and hoping for the best”. When \(M'\) sends a query of the form \((c,\sigma)\), \(Eve\) will first check if it happens to be the case that \((c,\sigma)\) was returned before as an answer to an encryption query \(m\). In this case \(Eve\) will breathe a sigh of relief and simply return \(m\) to \(M'\) as the answer. (This is obviously correct: if \((c,\sigma)\) is the encryption of \(m\) then \(m\) is the decryption of \((c,\sigma)\).) However, if the query \((c,\sigma)\) has not been returned before as an answer, then \(Eve\) is in a bit of a pickle. The way out of it is for her to simply return “error” and hope that everything will work out. The crucial observation is that because we are in case II things will work out. After all, the only way \(Eve\) makes a mistake is if she returns an error message where the original decryption box would not have done so, but this happens with probability at most \(\epsilon/10\). Hence, if \(M'\) has success \(1/2+\epsilon\) in the CCA game, then even if it’s the case that \(M'\) always outputs the wrong answer when \(Eve\) makes this mistake, we will still get success at least \(1/2+0.9\epsilon\). Since \(\epsilon\) is non negligible, this would contradict the CPA security of \((E,D)\) thereby concluding the proof of the theorem.

This proof is emblematic of a general principle for proving CCA security. The idea is to show that the decryption box is completely “useless” for the adversary, since the only way to get a non error response from it is to feed it with a ciphertext that was received from the encryption box.

(Simplified) GCM encryption

The construction above works as a generic construction, but it is somewhat costly in the sense that we need to evaluate both the block cipher and the MAC. In particular, if messages have \(t\) blocks, then we would need to invoke two cryptographic operations (a block cipher encryption and a MAC computation) per block. The GCM (Galois Counter Mode) is a way around this. We are going to describe a simplified version of this mode. For simplicity, assume that the number of blocks \(t\) is fixed and known (though many of the annoying but important details in block cipher modes of operations involve dealing with padding to multiple of blocks and dealing with variable block size).

A universal hash function collection is a family of functions \(\{ h:\{0,1\}^\ell\rightarrow\{0,1\}^n \}\) such that for every \(x \neq x' \in \{0,1\}^\ell\), the random variables \(h(x)\) and \(h(x')\) (taken over the choice of a random \(h\) from this family) are pairwise independent in \(\{0,1\}^{2n}\). That is, for every two potential outputs \(y,y'\in \{0,1\}^n\),

Universal hash functions have rather efficient constructions, and in particular if we relax the definition to allow almost universal hash functions (where we replace the \(2^{-2n}\) factor in the righthand side of Equation 6.1 by a slightly bigger, though still negligible quantity) then the constructions become extremely efficient and the size of the description of \(h\) is only related to \(n\), no matter how big \(\ell\) is.6

Our encryption scheme is defined as follow. The key is \((k,h)\) where \(k\) is an index to a pseudorandom permutation \(\{ p_k \}\) and \(h\) is the key for a universal hash function.7 To encrypt a message \(m = (m_1,\ldots,m_t) \in \{0,1\}^{nt}\) do the following:

Choose \(\ensuremath{\mathit{IV}}\) at random in \([2^n]\).

Let \(z_i = E_k(\ensuremath{\mathit{IV}}+i)\) for \(i=1,\ldots,t+1\).

Let \(c_i = z_i \oplus m_i\).

Let \(c_{t+1} = h(c_1,\ldots,c_t) \oplus z_{t+1}\).

Output \((\ensuremath{\mathit{IV}},c_1,\ldots,c_{t+1})\).

The communication overhead includes one additional output block plus the IV (whose transmission can often be avoided or reduced, depending on the settings; see the notion of “nonce based encryption”). This is fairly minimal. The additional computational cost on top of \(t\) block-cipher evaluation is the application of \(h(\cdot)\). For the particular choice of \(h\) used in Galois Counter Mode, this function \(h\) can be evaluated very efficiently- at a cost of a single multiplication in the Galois field of size \(2^{128}\) per block (one can think of it as some very particular operation that maps two \(128\) bit strings to a single one, and can be carried out quite efficiently). We leave it as an (excellent!) exercise to prove that the resulting scheme is CCA secure.

Padding, chopping, and their pitfalls: the “buffer overflow” of cryptography

In this course we typically focus on the simplest case where messages have a fixed size. But in fact, in real life we often need to chop long messages into blocks, or pad messages so that their length becomes an integral multiple of the block size. Moreover, there are several subtle ways to get this wrong, and these have been used in several practical attacks.

Chopping into blocks: A block cipher a-priori provides a way to encrypt a message of length \(n\), but we often have much longer messages and need to “chop” them into blocks. This is where the block cipher modes discussed in the previous lecture come in. However, the basic popular modes such as CBC and OFB do not provide security against chosen ciphertext attack, and in fact typically make it easy to extend a ciphertext with an additional block or to remove the last block from a ciphertext, both being operations which should not be feasible in a CCA secure encryption.

Padding: Oftentimes messages are not an integer multiple of the block size and hence need to be padded. The padding is typically a map that takes the last partial block of the message (i.e., a string \(m\) of length in \(\{0,\ldots,n-1\}\)) and maps it into a full block (i.e., a string \(m\in\{0,1\}^n\)). The map needs to be invertible which in particular means that if the message is already an integer multiple of the block size we will need to add an extra block. (Since we have to map all the \(1+2+\ldots+2^{n-1}\) messages of length \(1,\ldots,n-1\) into the \(2^n\) messages of length \(n\) in a one-to-one fashion.) One approach for doing so is to pad an \(n'<n\) length message with the string \(10^{n-n'-1}\). Sometimes people use a different padding which involves encoding the length of the pad.

Chosen ciphertext attack as implementing metaphors

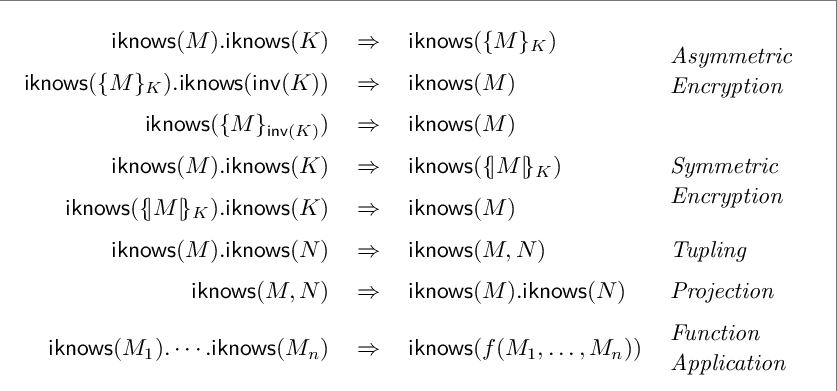

The classical “metaphor” for an encryption is a sealed envelope, but as we have seen in the WEP, this metaphor can lead you astray. If you placed a message \(m\) in a sealed envelope, you should not be able to modify it to the message \(m \oplus m'\) without opening the envelope, and yet this is exactly what happens in the canonical CPA secure encryption \(E_k(m)=(r,f_k(r) \oplus m)\). CCA security comes much closer to realizing the metaphor, and hence is considered as the “gold standard” of secure encryption. This is important even if you do not intend to write poetry about encryption. Formal verification of computer programs is an area that is growing in importance given that computer programs become both more complex and more mission critical. Cryptographic protocols can fail in subtle ways, and even published proofs of security can turn out to have bugs in them. Hence there is a line of research dedicated to finding ways to automatically prove security of cryptographic protocols. Much of these line of research is based on simple models to describe protocols that are known as Dolev Yao models, based on the first paper that proposed such models. These models define an algebraic form of security, where rather than thinking of messages, keys, and ciphertexts as binary string, we think of them as abstract entities. There are certain rules for manipulating these symbols. For example, given a key \(k\) and a message \(m\) you can create the ciphertext \(\{ m \}_k\), which you can decrypt back to \(m\) using the same key. However the assumption is that any information that cannot be obtained by such manipulation is unknown.

Translating a proof of security in this algebra to a proof for real world adversaries is highly non trivial. However, to have even a fighting chance, the encryption scheme needs to be as strong as possible, and in particular it turns out that security notions such as CCA play a crucial role.

Reading comprehension exercises

I recommend students do the following exercises after reading the lecture. They do not cover all material, but can be a good way to check your understanding.

Let \((E,D)\) be the “canonical” PRF-based CPA secure encryption, where \(E_k(m)= (r,f_k(r)\oplus m)\) and \(\{ f_k \}\) is a PRF collection and \(r\) is chosen at random. Is this scheme CCA secure?

No it is never CCA secure.

It is always CCA secure.

It is sometimes CCA secure and sometimes not, depending on the properties of the PRF \(\{ f_k \}\).

Suppose that we allow a key to be as long as the message, and so we can use the one time pad. Would the one-time pad be:

CPA secure

CCA secure

Neither CPA nor CCA secure.

Which of the following statements is true about the proof of Theorem 6.3:

Case I corresponds to breaking the MAC and Case II corresponds to breaking the CPA security of the underlying encryption scheme.

Case I corresponds to breaking the CPA security of the underlying encryption scheme and Case II corresponds to breaking the MAC.

Both cases correspond to both breaking the MAC and encryption scheme

If neither Case I nor Case II happens then we obtain an adversary breaking the security of the underlying encryption scheme.

- ↩

The PRG conjecture is the name we use in this course. In the literature this is known as the conjecture of the existence of pseudorandom generators, and through the work of Håstad, Impagliazzo, Levin and Luby (HILL) it is known to be equivalent to the existence of one way functions, see Vadhan, Chapter 7.

- ↩

This was done by Goldreich, Goldwasser and Micali.

- ↩

I also like the part where Green says about a block cipher mode that “if OCB was your kid, he’d play three sports and be on his way to Harvard.” We will have an exercise about a simplified version of the GCM mode (which perhaps only plays a single sport and is on its way to …). You can read about OCB in Exercise 9.14 in the Boneh-Shoup book; it uses the notion of a “tweakable block cipher” which simply means that given a single key \(k\), you actually get a set \(\{ p_{k,1},\ldots,p_{k,t} \}\) of permutations that are indistinguishable from \(t\) independent random permutation (the set \(\{1,\ldots, t\}\) is called the set of “tweaks” and we sometimes index it using strings instead of numbers).

- ↩

By a canonical verification algorithm we mean that \(V_k(m,\sigma)=1\) iff \(S_k(m)=\sigma\).

- ↩

Since we use a MAC with canonical verification, access to the signature algorithm implies access to the verification algorithm.

- ↩

In \(\epsilon\)-almost universal hash functions we require that for every \(y,y'\in \{0,1\}^{n}\), and \(x\neq x' \in \{0,1\}^\ell\), the probability that \(h(x)= h(x')\) is at most \(\epsilon\). It can be easily shown that the analysis below extends to \(\epsilon\) almost universal hash functions as long as \(\epsilon\) is negligible, but we will leave verifying this to the reader.

- ↩

In practice the key \(h\) is derived from the key \(k\) by applying the PRP to some particular input.

Comments

Comments are posted on the GitHub repository using the utteranc.es app. A GitHub login is required to comment. If you don't want to authorize the app to post on your behalf, you can also comment directly on the GitHub issue for this page.

Compiled on 11/17/2021 22:36:15

Copyright 2021, Boaz Barak.

This work is

licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Produced using pandoc and panflute with templates derived from gitbook and bookdown.