See any bugs/typos/confusing explanations? Open a GitHub issue. You can also comment below

★ See also the PDF version of this chapter (better formatting/references) ★

Public key cryptography

People have been dreaming about heavier-than-air flight since at least the days of Leonardo Da Vinci (not to mention Icarus from Greek mythology). Jules Verne wrote with rather insightful details about going to the moon in 1865. But, as far as I know, no one had considered the possibility of communicating securely without first exchanging a shared secret key until about 50 years ago. This is surprising given the thousands of years people have been using secret writing! However, in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, several people started to question this “common wisdom”.

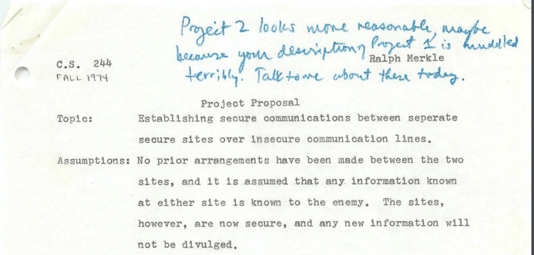

Perhaps the most surprising of these visionaries was an undergraduate student at Berkeley named Ralph Merkle. In the fall of 1974, he wrote a project proposal for his computer security course that while

“it might seem intuitively obvious that if two people have never had the opportunity to prearrange an encryption method, then they will be unable to communicate securely over an insecure channel… I believe it is false”.

Merkle also felt it is important to add “No. I am not joking.”. The project proposal was rejected by his professor as “not good enough”. Merkle later submitted a paper to the communication of the ACM, where he apologized for the lack of references since he was unable to find any mention of the problem in the scientific literature, and the only source where he saw the problem even raised was in a science fiction story. The paper was rejected with the comment that “Experience shows that it is extremely dangerous to transmit key information in the clear.” Merkle showed that one can design a protocol where Alice and Bob can use \(T\) invocations of a hash function to exchange a key, but an adversary (in the random oracle model, though he of course didn’t use this name) would need roughly \(T^2\) invocations to break it. He conjectured that it may be possible to obtain such protocols where breaking is exponentially harder than using them but could not think of any concrete way to doing so.

We only found out much later that in the late 1960’s, a few years before Merkle, James Ellis of the British Intelligence agency GCHQ was having similar thoughts. His curiosity was spurred by an old World War II manuscript from Bell labs that suggested the following way that two people could communicate securely over a phone line. Alice would inject noise to the line, Bob would relay his messages, and then Alice would subtract the noise to get the signal. The idea is that an adversary over the line sees only the sum of Alice’s and Bob’s signals and doesn’t know what came from what. This got James Ellis thinking whether it would be possible to achieve something like that digitally. As he later recollected, in 1970 he realized that in principle this should be possible. He could think of an hypothetical black box \(B\) that on input a “handle” \(\alpha\) and plaintext \(p\) would give a “ciphertext” \(c\). There would be a secret key \(\beta\) corresponding to \(\alpha\) such that feeding \(\beta\) and \(c\) to the box would recover \(p\). However, Ellis had no idea how to actually instantiate this box. He and others kept giving this question as a puzzle to bright new recruits until one of them, Clifford Cocks, came up in 1973 with a candidate solution loosely based on the factoring problem; in 1974 another GCHQ recruit, Malcolm Williamson, came up with a solution using modular exponentiation.

But among all those thinking of public key cryptography, probably the people who saw the furthest were two researchers at Stanford, Whit Diffie and Martin Hellman. They realized that with the advent of electronic communication, cryptography would find new applications beyond the military domain of spies and submarines. And they understood that in this new world of many users and point to point communication, cryptography would need to scale up. They envisioned an object which we now call “trapdoor permutation” though they called it “one way trapdoor function” or sometimes simply “public key encryption”. This is a collection of permutations \(\{ p_k \}\) where \(p_k\) is a permutation over (say) \(\{0,1\}^{|k|}\), and the map \((x,k)\mapsto p_k(x)\) is efficiently computable but the reverse map \((k,y) \mapsto p_k^{-1}(y)\) is computationally hard. Yet, there is also some secret key \(s(k)\) (i.e., the “trapdoor”) such that using \(s(k)\) it is possible to efficiently compute \(p^{-1}_k\). Their idea was that using such a trapdoor permutation, Alice who knows \(s(k)\) would be able to publish \(k\) on some public file such that everyone who wants to send her a message \(x\) could do so by computing \(p_k(x)\). (While today we know, due to the work of Goldwasser and Micali, that such a deterministic encryption is not a good idea, at the time Diffie and Hellman had amazing intuitions but didn’t really have proper definitions of security.) But they didn’t stop there. They realized that protecting the integrity of communication is no less important than protecting its secrecy. Thus, they imagined that Alice could “run encryption in reverse” in order to certify or sign messages. That is, given some message \(m\), Alice would send the value \(x=p_k^{-1}(h(m))\) (for a hash function \(h\)) as a way to certify that she endorses \(m\), and every person who knows \(k\) could verify this by checking that \(p_k(x)=h(m)\).

At this point, Diffie and Hellman were in a position similar to past physicists, who predicted that a certain particle should exist but had no experimental verification. Luckily they met Ralph Merkle. His ideas about a probabilistic key exchange protocol, together with a suggestion from their Stanford colleague John Gill, inspired them to come up with what today is known as the Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange (unbeknownst to them, a similar protocol was found two years earlier at GCHQ by Malcolm Williamson). They published their paper “New Directions in Cryptography” in 1976, and it is considered to have brought about the birth of modern cryptography. However, they still didn’t find their elusive trapdoor function. This was done the next year by Rivest, Shamir and Adleman who came up with the RSA trapdoor function, which through the framework of Diffie and Hellman yielded not just encryption but also signatures (this was essentially the same function discovered earlier by Clifford Cocks at GCHQ, though as far as I can tell Cocks, Ellis and Williamson did not realize the application to digital signatures). From this point on began a flurry of advances in cryptography which hasn’t really died down till this day.

Private key crypto recap

Before we embark on the wonderful journey to public key cryptography, let’s briefly look back and see what we learned about private key cryptography. This material is mostly covered in Chapters 1 to 9 of the Katz Lindell (KL) book and Part I (Chapters 1-9) of the Boneh Shoup (BS) book. Now would be a good time for you to read the corresponding proofs in one or both of these books. It is often helpful to see the same proof presented in a slightly different way. Below is a review of some of the various reductions we saw in class, with pointers to the corresponding sections in the Katz-Lindell (2nd ed) and Boneh-Shoup books. These are also covered in Rosulek’s book.

- Pseudorandom generators (PRG) length extension (from \(n+1\) output PRG to \(poly(n)\) output PRG): KL 7.4.2, BS 3.4.2

- PRG’s to pseudorandom functions (PRF’s): KL 7.5, BS 4.6

- PRF’s to Chosen Plaintext Attack (CPA) secure encryption: KL 3.5.2, BS 5.5

- PRF’s to secure Message Authentication Codes (MAC’s): KL 4.3, BS 6.3

- MAC’s + CPA secure encryption to chosen ciphertext attack (CCA) secure encryption: BS 4.5.4, BS 9.4

- Pseudorandom permutation (PRP’s) to CPA secure encryption / block cipher modes: KL 3.5.2, KL 3.6.2, BS 4.1, 4.4, 5.4

- Hash function applications: fingerprinting, Merkle trees, passwords: KL 5.6, BS Chapter 8

- Coin tossing over the phone: we saw a construction in class that used a commitment scheme built out of a pseudorandom generator. This is shown in BS 3.12, KL 5.6.5 shows an alternative construction using random oracles.

- PRP’s from PRF’s: we only sketched the construction which can be found in KL 7.6 or BS 4.5

One major point we did not talk about in this course was one way functions. The definition of a one way function is quite simple:

A function \(f:\{0,1\}^*\rightarrow\{0,1\}^*\) is a one way function if it is efficiently computable and for every \(n\) and a \(poly(n)\) time adversary \(A\), the probability over \(x\leftarrow_R\{0,1\}^n\) that \(A(f(x))\) outputs \(x'\) such that \(f(x')=f(x)\) is negligible.

The “OWF conjecture” is the conjecture that one way functions exist. It turns out to be a necessary and sufficient condition for much of private key cryptography. That is, the following theorem is known (by combining works of many people):

The following are equivalent:

One way functions exist

Pseudorandom generators (with non-trivial stretch) exist

Pseudorandom functions exist

CPA secure private key encryptions exist

CCA secure private key encryptions exist

Message Authentication Codes exist

Commitment schemes exist

The key result in the proof of this theorem is the result of Hastad, Impagliazzo, Levin and Luby that if one way functions exist then pseudorandom generators exist. If you are interested in finding out more, see Chapter 7 in Vadhan’s pseudorandomness monograph. Sections 7.2-7.4 in the KL book also cover a special case of this theorem for the case that the one way function is a permutation on \(\{0,1\}^n\) for every \(n\). This proof has been considerably simplified and quantitatively improved in works of Haitner, Holenstein, Reingold, Vadhan, Wee and Zheng. See this talk of Salil Vadhan for more on this. See also these lecture notes from a Princeton seminar I gave on this topic (though the proof has been simplified since then by the above works).

Another topic we did not discuss in depth is attacks on private key cryptosystems. These attacks often work by “opening the black box” and looking at the internal operation of block ciphers or hash functions. We then assign variables to various internal registers, and look to find collections of inputs that would satisfy some non-trivial relation between those variables. This is a rather vague description, but you can read KL Section 6.2.6 on linear and differential cryptanalysis and BS Sections 3.7-3.9 and 4.3 for more information. See also this course of Adi Shamir, and the courses of Dunkelman on analyzing block ciphers and hash functions. There is also the fascinating area of side channel attacks on both public and private key crypto, see this course of Tromer.

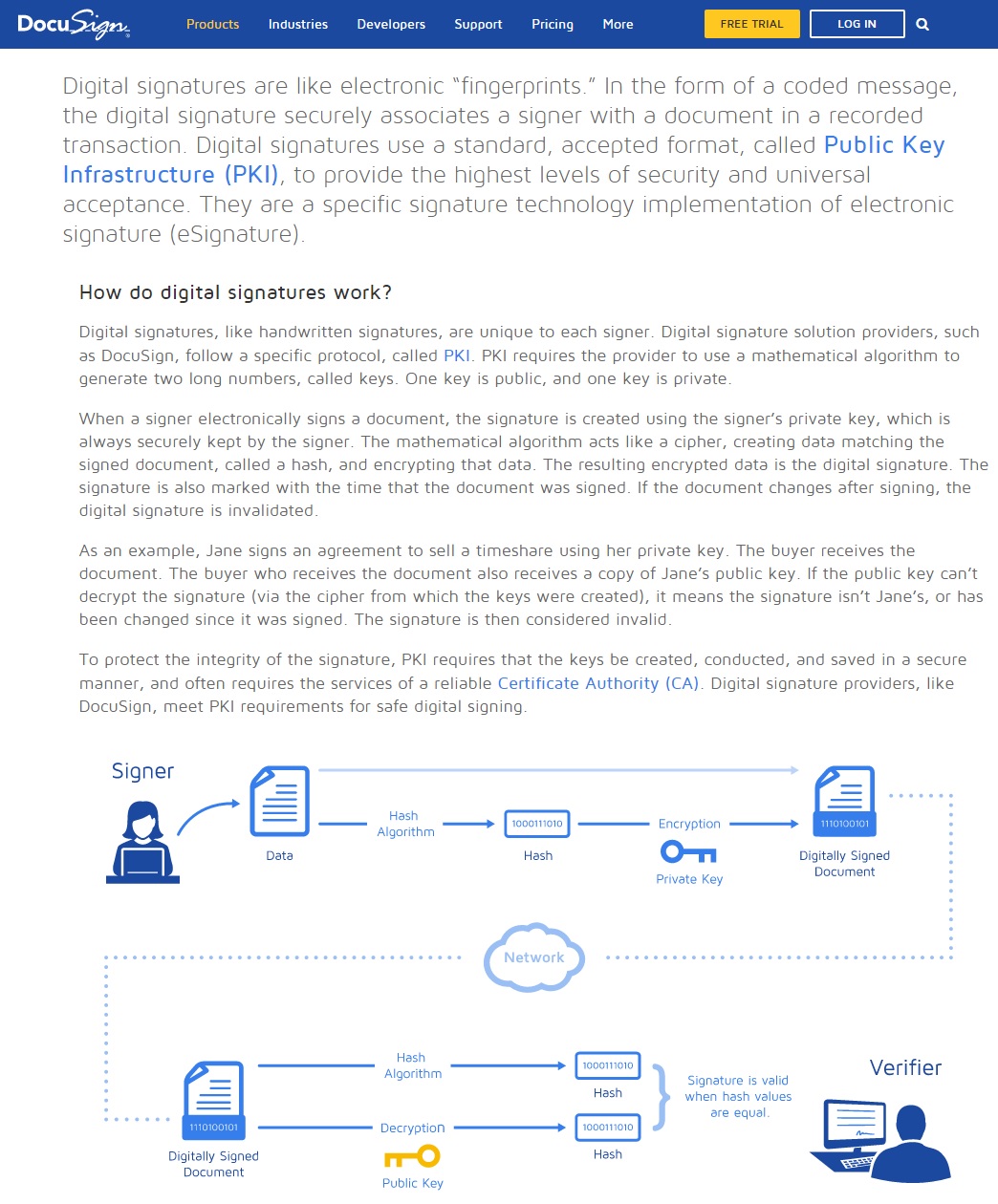

We will discuss in this lecture Digital signatures, which are the public key analog of message authentication codes. Surprisingly, despite being a “public key” object, it is possible to base digital signatures on one-way functions (this is obtained using ideas of Lamport, Merkle, Goldwasser-Goldreich-Micali, Naor-Yung, and Rompel). However these constructions are not very efficient (and this may be inherent), and so in practice people use digital signatures that are built using similar techniques to those used for public key encryption.

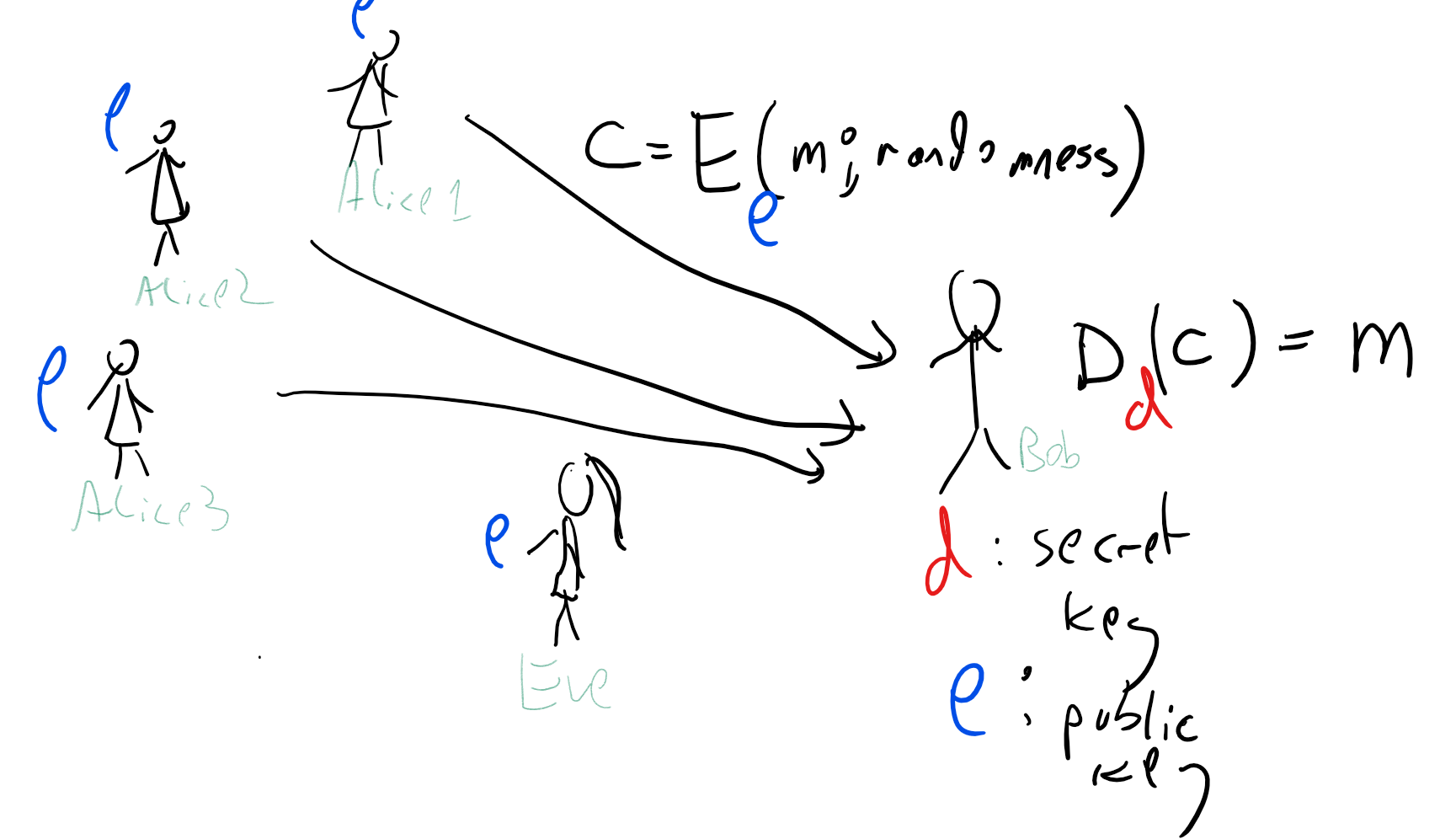

Public Key Encryptions: Definition

We now discuss how we define security for public key encryption. As mentioned above, it took quite a while for cryptographers to arrive at the “right” definition, but in the interest of time we will skip ahead to what by now is the standard basic notion (see also Figure 9.3):

A triple of efficient algorithms \((G,E,D)\) is a public key encryption scheme of length function \(\ell:\N \rightarrow \N\) if it satisfies the following:

\(G\) is a probabilistic algorithm known as the key generation algorithm that on input \(1^n\) outputs a distribution over pair of keys \((e,d)\).

\(E\) is the encryption algorithm that takes a pair of inputs \(e,m\) with \(m\in \{0,1\}^{\ell(n)}\) and outputs \(c=E_e(m)\).

\(D\) is the decryption algorithm that takes a pair of inputs \(d,c\) and outputs \(m'=D_d(c)\).

For every \(m\in\{0,1\}^{\ell(n)}\), with probability \(1-negl(n)\) over the choice of \((e,d)\) output from \(G(1^n)\) and the coins of \(E\),\(D\), \(D_d(E_e(m))=m\).

Definition 9.5 just refers to the validity of a public-key encryption scheme, namely the condition that we can encrypt and decrypt using the keys \(e\) and \(d\) respectively, but not to its security. The standard definition of security for public-key encryption is CPA security:

We say that \((G,E,D)\) is CPA secure if every efficient adversary \(A\) wins the following game with probability at most \(1/2+negl(n)\):

\((e,d) \leftarrow_R G(1^n)\)

\(A\) is given \(e\) and outputs a pair of messages \(m_0,m_1 \in \{0,1\}^n\).

\(A\) is given \(c=E_e(m_b)\) for \(b\leftarrow_R\{0,1\}\).

\(A\) outputs \(b'\in\{0,1\}\) and wins if \(b'=b\).

Despite it being a “chosen plaintext attack”, we don’t explicitly give \(A\) access to the encryption oracle in the public key setting. Make sure you understand why giving it such access would not give it more power.

One metaphor for a public key encryption is a “self-locking lock” where you don’t need the key to lock it (but rather you simply push the shackle until it clicks and lock), but you do need the key to unlock it. So, if Alice generates \((e,d)=G(1^n)\), then \(e\) serves as the “lock” that can be used to encrypt messages for Alice while only \(d\) can be used to decrypt the messages. Another way to think about it is that \(e\) is a “hobbled key” that can be used for only some of the functions of \(d\).

The obfuscation paradigm

Why would someone imagine that such a magical object could exist? The writing of both James Ellis as well as Diffie and Hellman suggests that their thought process was roughly as follows. You imagine a “magic black box” \(B\) such that if all parties have access to \(B\) then we could get a public key encryption scheme. Now if public key encryption was impossible it would mean that for every possible program \(P\) that computes the functionality of \(B\), if we distribute the code of \(P\) to all parties, then we don’t get a secure encryption scheme. That means that no matter what program \(P\) the adversary gets, she will always be able to get some information out of that code that helps break the encryption, even though she wouldn’t have been able to break it if \(P\) was a black box. Now, intuitively understanding arbitrary code is a very hard problem, so Diffie and Hellman imagined that it might be possible to take this ideal \(B\) and compile it to some sufficiently low level assembly language so that it would behave as a “virtual black box”.

In particular, if you took, say, the encoding procedure \(m \mapsto p_k(m)\) of a block cipher with a particular key \(k\) and ran it through an optimizing compiler, you might hope that while it would be possible to perform this map using the resulting executable, it will be hard to extract \(k\) from it. Hence, you could treat this code as a “public key”. This suggests the following approach for getting an encryption scheme:

“Obfuscation based public key encryption”: (Thought experiment - not an actual construction)

Ingredients:

(i) A pseudorandom permutation collection \(\{ p_k \}_{k\in \{0,1\}^*}\) where for every \(k\in \{0,1\}^n\), \(p_k:\{0,1\}^n \rightarrow \{0,1\}^n\)

(ii) An “obfuscating compiler” polynomial-time computable \(O:\{0,1\}^* \rightarrow \{0,1\}^*\) such that for every circuit \(C\), \(O(C)\) is a circuit that computes the same function as \(C\).

Operation:

Key Generation: The private key is \(k \leftarrow_R \{0,1\}^n\), the public key is \(E=O(C_k)\) where \(C_k\) is the circuit that maps \(x\in \{0,1\}^n\) to \(p_k(x)\).

Encryption: To encrypt \(m\in \{0,1\}^n\) with public key \(E\), choose \(\ensuremath{\mathit{IV}} \leftarrow_R \{0,1\}^n\) and output \((\ensuremath{\mathit{IV}}, E(x \oplus \ensuremath{\mathit{IV}}))\).

Decryption: To decrypt \((\ensuremath{\mathit{IV}},y)\) with key \(k\), output \(\ensuremath{\mathit{IV}} \oplus p_k^{-1}(y)\).

Diffie and Hellman couldn’t really find a way to make this work, but it convinced them this notion of public key is not inherently impossible. This concept of compiling a program into a functionally equivalent but “inscrutable” form is known as software obfuscation. It had turned out to be quite a tricky object to both define formally and achieve, but it serves as very good intuition for what can be achieved, even if, as with the random oracle, this intuition can sometimes be too optimistic. (Indeed, if software obfuscation was possible then we could obtain a “random oracle like” hash function by taking the code of a function \(f_k\) chosen from a PRF family and compiling it through an obfuscating compiler.)

We will not formally define obfuscators yet, but on an intuitive level it would be a compiler that takes a program \(P\) and maps into a program \(P'\) such that:

- \(P'\) is not much slower/bigger than \(P\) (e.g., as a Boolean circuit it would be at most polynomially larger).

- \(P'\) is functionally equivalent to \(P\), i.e., \(P'(x)=P(x)\) for every input \(x\).1

- \(P'\) is “inscrutable” in the sense that seeing the code of \(P'\) is not more informative than getting black box access to \(P\).

Let me stress again that there is no known construction of obfuscators achieving something similar to this definition. In fact, the most natural formalization of this definition is impossible to achieve (as we might see later in this course). Only very recently (exciting!) progress was finally made towards obfuscators-like notions strong enough to achieve these and other applications, and there are some significant caveats, see my survey on this topic and a more recent Quanta article.

However, when trying to stretch your imagination to consider the amazing possibilities that could be achieved in cryptography, it is not a bad heuristic to first ask yourself what could be possible if only everyone involved had access to a magic black box. It certainly worked well for Diffie and Hellman.

Some concrete candidates:

We would have loved to prove a theorem of the form:

“Theorem”: If the PRG conjecture is true, then there exists a CPA-secure public key encryption.

This would have meant that we do not need to assume anything more than the already minimal notion of pseudorandom generators (or equivalently, one way functions) to obtain public key cryptography. Unfortunately, no such result is known (and this may be inherent). The kind of results we know have the following form:

Theorem: If problem \(X\) is hard, then there exists a CPA-secure public key encryption.

Here, \(X\) is some problem that people have tried to solve and couldn’t. Thus, we have various candidates for public key encryption, and we fervently hope that at least one of them is actually secure. The dirty little secret of cryptography is that we actually don’t have that many candidates. We really have only two well studied families.2 One is the “group theoretic” family that relies on the difficulty of the discrete logarithm (over modular arithmetic or elliptic curves) or the integer factoring problem. The other is the “coding/lattice theoretic” family that relies on the difficulty of solving noisy linear equations or related problems such as finding short vectors in a lattice and solving instances of the “knapsack” problem. Moreover, problems from the first family are known to be efficiently solvable in a computational model known as “quantum computing”. If large scale physical devices that simulate this model, known as quantum computers, exist, then they could break all cryptosystems relying on these problems, and we’ll be down to only having a single family of candidate public key encryption schemes.

We will start by describing cryptosystems based on the first family (which was discovered before the other and was more widely implemented), and talk about the second family in future lectures.

Diffie-Hellman Encryption (aka El-Gamal)

The Diffie-Hellman public key system is built on the presumed difficulty of the discrete logarithm problem:

For any number \(p\), let \(\Z_p\) be the set of numbers \(\{0,\ldots,p-1\}\) where addition and multiplication are done modulo \(p\). We will think of numbers \(p\) that are of magnitude roughly \(2^n\), so they can be described with about \(n\) bits. We can clearly multiply and add such numbers modulo \(p\) in \(poly(n)\) time. If \(g\in \Z_p\) and \(a\) is any natural number, we can define \(g^a\) to be simply \(g\cdot g \cdots g\) (\(a\) times). A priori one might think that it would take \(a\cdot poly(n)\) time to compute \(g^a\), which might be exponential if \(a\) itself is roughly \(2^n\). However, we can compute this in \(poly((\log a) \cdot n)\) time using the repeated squaring trick. The idea is that if \(a=2^{\ell}\), then we can compute \(g^a\) in \(\ell\) by squaring \(g\) \(\ell\) times, and a general \(a\) can be decomposed into powers of two using the binary representation.

The discrete logarithm problem is the problem of computing, given \(g,h \in \Z_p\), a number \(a\) such that \(g^a=h\). If such a solution \(a\) exists then there is always also a solution of size at most \(p\) (can you see why?) and so the solution can be represented using \(n\) bits. However, currently the best-known algorithm for computing the discrete logarithm runs in time roughly \(2^{n^{1/3}}\), which is currently prohibitively expensive when \(p\) is a prime of length about \(2048\) bits.3

John Gill suggested to Diffie and Hellman that modular exponentiation can be a good source for the kind of “easy-to-compute but hard-to-invert” functions they were looking for. Diffie and Hellman based a public key encryption scheme as follows:

- The key generation algorithm, on input \(n\), samples a prime number \(p\) of \(n\) bits description (i.e., between \(2^{n-1}\) to \(2^n\)), a number \(g\leftarrow_R \Z_p\) and \(a \leftarrow_R \{0,\ldots,p-1\}\). We also sample a hash function \(H:\{0,1\}^n\rightarrow\{0,1\}^\ell\). The public key \(e\) is \((p,g,g^a,H)\), while the secret key \(d\) is \(a\).4

The encryption algorithm, on input a message \(m \in \{0,1\}^\ell\) and a public key \(e=(p,g,h,H)\), will choose a random \(b\leftarrow_R \{0,\ldots,p-1\}\) and output \((g^b,H(h^b)\oplus m)\).

The decryption algorithm, on input a ciphertext \((f,y)\) and the secret key, will output \(H(f^a) \oplus y\).

The correctness of the decryption algorithm follows from the fact that \((g^a)^b = (g^b)^a = g^{ab}\) and hence \(H(h^b)\) computed by the encryption algorithm is the same as the value \(H(f^a)\) computed by the decryption algorithm. A simple relation between the discrete logarithm and the Diffie-Hellman system is the following:

If there is a polynomial time algorithm for the discrete logarithm problem, then the Diffie-Hellman system is insecure.

Using a discrete logarithm algorithm, we can compute the private key \(a\) from the parameters \(p,g,g^a\) present in the public key, and clearly once we know the private key we can decrypt any message of our choice.

Unfortunately, no such result is known in the other direction. However, we can prove that this protocol is secure in the random-oracle model, under the assumption that the task of computing \(g^{ab}\) from \(g^a\) and \(g^b\) (which is now known as the Diffie-Hellman problem) is hard.

Computational Diffie-Hellman Assumption: Let \(\mathbb{G}\) be a group whose elements can be described in \(n\) bits, with an associative and commutative multiplication operation that can be computed in \(poly(n)\) time. The Computational Diffie-Hellman (CDH) assumption holds with respect to the group \(\mathbb{G}\) if for every generator (see below) \(g\) of \(\mathbb{G}\) and efficient algorithm \(A\), the probability that on input \(g,g^a,g^b\), \(A\) outputs the element \(g^{ab}\) is negligible as a function of \(n\).5

In particular we can make the following conjecture:

Computational Diffie-Hellman Conjecture for mod prime groups: For a random \(n\)-bit prime and random \(g \in \mathbb{Z}_p\), the CDH holds with respect to the group \(\mathbb{G} = \{ g^a \mod p \;| a\in \mathbb{Z} \}\).

That is, for every polynomial \(q:\N \rightarrow \N\), if \(n\) is large enough, then with probability at least \(1-1/q(n)\) over the choice of a uniform prime \(p\in [2^n]\) and \(g\in \Z_p\), for every circuit \(A\) of size at most \(q(n)\), the probability that \(A(g,p,g^a,g^b)\) outputs \(h\) such that \(g^{ab} = h \mod p\) is at most \(1/q(n)\) where the probability is taken over \(a,b\) chosen at random in \(\Z_p\). (In practice people often take \(g\) to be a generator of a group significantly smaller in size than \(p\), which enables \(a,b\) to be smaller numbers and hence multiplication to be more efficient; we ignore this optimization in our discussions.)

Please take your time to re-read the following conjecture until you are sure you understand what it means. Victor Shoup’s excellent and online available book A Computational Introduction to Number Theory and Algebra has an in depth treatment of groups, generators, and the discrete log and Diffie-Hellman problem. See also Chapters 10.4 and 10.5 in the Boneh-Shoup book, and Chapters 8.3 and 11.4 in the Katz-Lindell book. There are also solved group theory exercises at the end of this chapter.

Suppose that the Computational Diffie-Hellman Conjecture for mod prime groups is true. Then, the Diffie-Hellman public key encryption is CPA secure in the random oracle model.

For CPA security we need to prove that (for fixed \(\mathbb{G}\) of size \(p\) and random oracle \(H\)) the following two distributions are computationally indistinguishable for every two strings \(m,m' \in \{0,1\}^\ell\):

\((g^a,g^b,H(g^{ab})\oplus m)\) for \(a,b\) chosen uniformly and independently in \(\Z_{p}\).

\((g^a,g^b,H(g^{ab})\oplus m')\) for \(a,b\) chosen uniformly and independently in \(\Z_{p}\).

(can you see why this implies CPA security? you should pause here and verify this!)

We make the following claim:

CLAIM: For a fixed \(\mathbb{G}\) of size \(p\), generator \(g\) for \(\mathbb{G}\), and given random oracle \(H\), if there is a size \(T\) distinguisher \(A\) with \(\epsilon\) advantage between the distribution \((g^a,g^b,H(g^{ab}))\) and the distribution \((g^a,g^b,U_\ell)\) (where \(a,b\) are chosen uniformly and independently in \(\Z_{p}\)), then there is a size \(poly(T)\) algorithm \(A'\) to solve the Diffie-Hellman problem with respect to \(\mathbb{G},g\) with success at least \(\epsilon\). That is, for random \(a,b \in \Z_p\), \(A'(g,g^a,g^b)=g^{ab}\) with probability at least \(\epsilon/(2T)\).

Proof of claim: The proof is simple. We claim that under the assumptions above, \(A\) makes the query \(g^{ab}\) to its oracle \(H\) with probability at least \(\epsilon/2\) since otherwise, by the “lazy evaluation” paradigm, we can assume that \(H(g^{ab})\) is chosen independently at random after \(A\)’s attack is completed and hence (conditioned on the adversary not making that query), the value \(H(g^{ab})\) is indistinguishable from a uniform output. Therefore, on input \(g,g^a,g^b\), \(A'\) can simulate \(A\) and simply output one of the at most \(T\) queries that \(A\) makes to \(H\) at random and will be successful with probability at least \(\epsilon/(2T)\).

Now given the claim, we can complete the proof of security via the following hybrids. Define the following “hybrid” distributions (where in all cases \(a,b\) are chosen uniformly and independently in \(\Z_{p}\)):

\(H_0\): \((g^a,g^b,H(g^{ab}) \oplus m)\)

\(H_1\): \((g^a,g^b,U_\ell \oplus m)\)

\(H_2\): \((g^a,g^b,U_\ell \oplus m')\)

\(H_3\): \((g^a,g^b,H(g^{ab}) \oplus m')\)

The claim implies that \(H_0 \approx H_1\). Indeed otherwise we could transform a distinguisher \(T\) between \(H_0\) and \(H_1\) to a distinguisher \(T'\), violating the claim by letting \(T'(h,h',z) = T(h,h',z \oplus m)\).

The distributions \(H_1\) and \(H_2\) are identical by the same argument as the security of the one time pad (since \(U_\ell \oplus m\) is identical to \(U_\ell\)).

The distributions \(H_2\) and \(H_3\) are computationally indistinguishable by the same argument that \(H_0 \approx H_1\).

Together these imply that \(H_0 \approx H_3\) which yields the CPA security of the scheme.

One can get security results for this protocol without a random oracle if we assume a stronger variant known as the Decisional Diffie-Hellman (DDH) assumption: for a random \(a,b, u \in \mathbb{Z}_p\) (prime \(p\)), the triple \((g^a, g^b, g^{ab})\approx (g^a, g^b, g^u)\). This implies CDH (can you see why?). DDH also restricts our focus to groups of prime order. In particular, DDH does not hold in even-order groups. For example, DDH does not hold in \(\mathbb{Z}^{\*}_p=\{1,2\ldots p-1\}\) (with group operation multiplication mod \(p\)) since half of its elements are quadratic residues and it is efficient to test if an element is a quadratic residue using Fermat’s little theorem (can you see why? See Exercise 10.7). However, DDH holds in subgroups of \(\mathbb{Z}^{\*}_p\) of prime order. If \(p\) is a safe prime (i.e. \(p=2q+1\) for a prime \(q\)), then we can instead use the subgroup of quadratic residues, which has prime order \(q\). See Boneh-Shoup 10.4.1 for more details on the underlying groups for CDH and DDH.

As mentioned, the Diffie-Hellman systems can be run with many variants of Abelian groups. Of course, for some of those groups the discrete logarithm problem might be easy, and so they would be inappropriate to use for this system. One variant that has been proposed is elliptic curve cryptography. This is a group consisting of points of the form \((x,y,z)\in \Z_p^3\) that satisfy a certain equation, where multiplication can be defined in a certain way. The main advantage of elliptic curve cryptography is that the best known algorithms run in time \(2^{\approx n}\) as opposed to \(2^{\approx n^{1/3}}\), which allows for much shorter keys. Unfortunately, elliptic curve cryptography is just as susceptible to quantum algorithms as the discrete logarithm problem over \(\Z_p\).

In most of the cryptography literature the protocol above is called the Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange protocol, and when considered as a public key system it is sometimes known as ElGamal encryption.6 The reason for this mostly stems from the early confusion on what the right security definitions are. Diffie and Hellman thought of encryption as a deterministic process and so they called their scheme a “key exchange protocol”. The work of Goldwasser and Micali showed that encryption must be probabilistic for security. Also, because of efficiency considerations, these days public key encryption is mostly used as a mechanism to exchange a key for a private key encryption that is then used for the bulk of the communication. Together this means that there is not much point in distinguishing between a two-message key exchange algorithm and a public key encryption.

Sampling random primes

To sample a random \(n\) bit prime, one can sample a random number \(0 \leq p < 2^n\) and then test if \(p\) is prime. If it is not prime, then we can sample a new random number again. To make this work we need to show two properties:

Efficient testing: That there is a \(poly(n)\) time algorithm to test whether an \(n\) bit number is a prime. It turns out that there are such known algorithms. Randomized algorithm have been known since the 1970’s. Moreover in a 2002 breakthrough, Manindra Agrawal, Neeraj Kayal, and Nitin Saxena (a professor and two undergraduate students from the Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur) came up with the first deterministic polynomial time algorithm for testing primality.

Prime density: That the probability that a random \(n\) bit number is prime is at least \(1/poly(n)\). This probability is in fact \(1/\ln(2^n)=\Omega(1/n)\) by the Prime Number Theorem. However, for the sake of completeness, we sketch below a simple argument showing the probability is at least \(\Omega(1/n^2)\).

The number of primes between \(1\) and \(N\) is \(\Omega(N/\log N)\).

Recall that the least common multiple (LCM) of two or more \(a_1,\ldots,a_t\) is the smallest number that is a multiple of all of the \(a_i\)’s. One way to compute the LCM of \(a_1,\ldots,a_t\) is to take the prime factorizations of all the \(a_i\)’s, and then the LCM is the product of all the primes that appear in these factorizations, each taken to the corresponding highest power that appears in the factorization. Let \(k\) be the number of primes between \(1\) and \(N\). The lemma will follow from the following two claims:

CLAIM 1: \(\ensuremath{\mathit{LCM}}(1,\ldots,N) \leq N^k\).

CLAIM 2: If \(N\) is odd, then \(\ensuremath{\mathit{LCM}}(1,\ldots,N) \geq 2^{N-1}\).

The two claims immediately imply the result, since they imply that \(2^{N-1} \leq N^k\), and taking logs we get that \(N-1 \leq k \log N\) or \(k \geq (N-1)/\log N\). (We can assume that \(N\) is odd without of loss of generality, since changing from \(N\) to \(N+1\) can change the number of primes by at most one.) Thus, all that is left is to prove the two claims.

Proof of CLAIM 1: Let \(p_1,\ldots,p_k\) be all the prime numbers between \(1\) and \(N\), and let \(e_i\) be the largest integer such that \(p_i^{e_i} \leq N\) and \(L = p_1^{e_1} \cdots p_k^{e_k}\). Since \(L\) is the product of \(k\) terms, each of size at most \(N\), \(L \leq N^k\). But we claim that every number \(1 \leq a \leq N\) divides \(L\). Indeed, every prime \(p\) in the prime factorization of \(a\) is one of the \(p_i\)’s, and since \(a \leq N\), the power in which \(p\) appears in \(a\) is at most \(e_i\). By the definition of the least common multiple, this means that \(\ensuremath{\mathit{LCM}}(1,\ldots,N) \leq L\). QED (CLAIM 1)

Proof of CLAIM 2: Consider the integral \(I=\int_0^1 x^{(N-1)/2}(1-x)^{(N-1)/2} dx\). This is clearly some positive number and so \(I>0\). On one hand, for every \(x\) between zero and one, \(x(1-x) \leq 1/4\) and hence \(I\) is at most \(4^{-(N-1)/2}=2^{-N+1}\). On the other hand, the polynomial \(x^{(N-1)/2}(1-x)^{(N-1)/2}\) is some polynomial of degree at most \(N-1\) with integer coefficients, and so \(I=\sum_{k=0}^{N-1} C_k \int_0^1 x^k dx\) for some integer coefficients \(C_0,\ldots,C_{N-1}\). Since \(\int_0^1 x^k dx = \tfrac{1}{k+1}\), we see that \(I\) is a sum of fractions with integer numerators and with denominators that are at most \(N\). Since all the denominators are at most \(N\) and \(I>0\), it follows that \(I \geq \tfrac{1}{LCM(1,\ldots,N)}\), and so

A little bit of group theory.

If you haven’t seen group theory, it might be useful for you to do a quick review. We will not use much group theory and mostly use the theory of finite commutative (also known as Abelian) groups (in fact often cyclic) which are such a baby version that it might not be considered true “group theory” by many group theorists. Shoup’s excellent book contains everything we need to know (and much more than that). What you need to remember is the following:

A finite commutative group \(\mathbb{G}\) is a finite set together with a multiplication operation that satisfies \(a\cdot b = b\cdot a\) and \((a\cdot b)\cdot c = a\cdot (b\cdot c)\).

\(\mathbb{G}\) has a special element known as \(1\), where \(g1=1g=g\) for every \(g\in\mathbb{G}\) and for every \(g\in \mathbb{G}\) there exists an element \(g^{-1}\in \mathbb{G}\) such that \(gg^{-1}=1\).

For every \(g\in \mathbb{G}\), the order of \(g\), denoted \(order(g)\), is the smallest positive integer \(a\) such that \(g^a=1\).

The following basic facts are all not too hard to prove and would be useful exercises:

For every \(g\in \mathbb{G}\), the map \(a \mapsto g^a\) is a \(k\) to \(1\) map from \(\{0,\ldots,|\mathbb{G}|-1\}\) to \(\mathbb{G}\) where \(k=|\mathbb{G}|/order(g)\). See footnote for hint.7

As a corollary, the order of \(g\) is always a divisor of \(|\mathbb{G}|\). This is a special case of a more general phenomenon: the set \(\{ g^a \;|\; a\in\mathbb{Z} \}\) is a subset of the group \(\mathbb{G}\) that is closed under multiplication, and such subsets are known as subgroups of \(\mathbb{G}\). It is not hard to show (using the same approach as above) that for every group \(\mathbb{G}\) and subgroup \(\mathbb{H}\), the size of \(\mathbb{H}\) divides the size of \(\mathbb{G}\). This is known as Lagrange’s Theorem in group theory.

An element \(g\) of \(\mathbb{G}\) is called a generator if \(order(g)=|\mathbb{G}|\). A group is called cyclic if it has a generator. If \(\mathbb{G}\) is cyclic then there is a (not necessarily efficiently computable) isomorphism \(\phi:\mathbb{G}\rightarrow\Z_{|\mathbb{G}|}\) which is a one-to-one and onto map satisfying \(\phi(g\cdot h)=\phi(g)+\phi(h)\) for every \(g,h\in\mathbb{G}\).

When using a group \(\mathbb{G}\) for the Diffie-Hellman protocol, we want the property that \(g\) is a generator of the group, which also means that the map \(a \mapsto g^a\) is a one-to-one mapping from \(\{0,\ldots,|\mathbb{G}|-1\}\) to \(\mathbb{G}\). This can be efficiently tested if we know the order of the group and its factorization, since it will occur if and only if \(g^a \neq 1\) for every \(a<|\mathbb{G}|\) (can you see why this holds?) and we know that if \(g^a=1\) then \(a\) must divide \(\mathbb{G}\) (and this?).

It is not hard to show that a random element \(g\in \mathbb{G}\) will be a generator with non-trivial probability (for similar reasons that a random number is prime with non-trivial probability). Hence, an approach to getting such a generator is to simply choose \(g\) at random and test that \(g^a \neq 1\) for all of the fewer than \(\log |\mathbb{G}|\) numbers that are obtained by taking \(|\mathbb{G}|/q\) where \(q\) is a factor of \(|\mathbb{G}|\).

Try to stop here and verify all the facts on groups mentioned above. There are additional group theory exercises at the end of the chapter as well.

Digital Signatures

Public key encryption solves the confidentiality problem, but we still need to solve the authenticity or integrity problem, which might be even more important in practice. That is, suppose Alice wants to endorse a message \(m\) that everyone can verify, but only she can sign. This of course is extremely widely used in many settings, including software updates, web pages, financial transactions, and more.

A triple of algorithms \((G,S,V)\) is a chosen-message-attack secure digital signature scheme if it satisfies the following:

On input \(1^n\), the probabilistic key generation algorithm \(G\) outputs a pair \((s,v)\) of keys, where \(s\) is the private signing key and \(v\) is the public verification key.

On input a message \(m\) and the signing key \(s\), the signing algorithm \(S\) outputs a string \(\sigma = S_{s}(m)\) such that with probability \(1-negl(n)\), \(V_v(m,S_s(m))=1\).

Every efficient adversary \(A\) wins the following game with at most negligible probability:

The keys \((s,v)\) are chosen by the key generation algorithm.

The adversary gets the inputs \(1^n\), \(v\), and black box access to the signing algorithm \(S_s(\cdot)\).

The adversary wins if they output a pair \((m^*,\sigma^*)\) such that \(m^*\) was not queried before to the signing algorithm and \(V_v(m^*,\sigma^*)=1\).

Just like for MACs (see Definition 4.8), our definition of security for digital signatures with respect to a chosen message attack does not preclude the ability of the adversary to produce a new signature for the same message that it has seen a signature of. Just like in MACs, people sometimes consider the notion of strong unforgeability which requires that it would not be possible for the adversary to produce a new message-signature pair (even if the message itself was queried before). Some signature schemes (such as the full domain hash and the DSA scheme) satisfy this stronger notion while others do not. However, just like MACs, it is possible to transform any signature with standard security into a signature that satisfies this stronger unforgeability condition.

The Digital Signature Algorithm (DSA)

The Diffie-Hellman protocol can be turned into a signature scheme. This was first done by ElGamal, and a variant of his scheme was developed by the NSA and standardized by NIST as the Digital Signature Algorithm (DSA) standard. When based on an elliptic curve this is known as ECDSA. The starting point is the following generic idea of how to turn an encryption scheme into an identification protocol.

If Alice published a public encryption key \(e\), then one natural approach for Alice to prove her identity to Bob is as follows. Bob will send an encryption \(c=E_e(x)\) of some random message \(x \leftarrow_R \{0,1\}^n\) to Alice, and Alice will send \(x'=D_d(c)\) back. If \(x=x'\), then she has proven that she can decrypt ciphertexts encrypted with \(e\), and so Bob can be assured that she is the rightful owner of the public key \(e\).

However, this falls short of a signature scheme in two aspects:

This is only an identification protocol and does not allow Alice to endorse a particular message \(m\).

This is an interactive protocol, and so Alice cannot generate a static signature based on \(m\) that can be verified by any party without further interaction.

The first issue is not so significant, since we can always have the ciphertext be an encryption of \(x=H(m)\) where \(H\) is some hash function presumed to behave as a random oracle. (We do not want to simply run this protocol with \(x=m\). Can you see why?)

The second issue is more serious. We could imagine Alice trying to run this protocol on her own by generating the ciphertext and then decrypting it, and then sending over the transcript to Bob. But this does not really prove that she knows the corresponding private key. After all, even without knowing \(d\), any party can generate a ciphertext \(c\) and its corresponding decryption. The idea behind the DSA protocol is that we require Alice to generate a ciphertext \(c\) and its decryption satisfying some additional extra conditions, which would prove that Alice truly knew the secret key.

DSA Signatures: The DSA signature algorithm works as follows: (See also Section 12.5.2 in the KL book)

Key generation: Pick generator \(g\) for \(\mathbb{G}\) and \(a\in \{0,\ldots,|\mathbb{G}|-1\}\) and let \(h=g^a\). Pick \(H:\{0,1\}^\ell\rightarrow\mathbb{G}\) and \(F:\mathbb{G}\rightarrow\mathbb{G}\) to be some functions that can be thought of as “hash functions”.8 The public key is \((g,h)\) (as well as the functions \(H,F\)) and secret key is \(a\).

Signature: To sign a message \(m\) with the key \(a\), pick \(b\) at random, and let \(f=g^b\), and then let \(\sigma = b^{-1}[H(m)+a\cdot F(f)]\), where all computation is done modulo \(|\mathbb{G}|\). The signature is \((f,\sigma)\).

Verification: To verify a signature \((f,\sigma)\) on a message \(m\), check that \(\sigma\neq 0\) and \(f^\sigma=g^{H(m)}h^{F(f)}\).

You should pause here and verify that this is indeed a valid signature scheme, in the sense that for every \(m\), \(V_s(m,S_s(m))=1\).

Very roughly speaking, the idea behind security is that on one hand \(\sigma\) does not reveal information about \(b\) and \(a\) because this is “masked” by the “random” value \(H(m)\). On the other hand, if an adversary is able to come up with valid signatures, then at least if we treated \(H\) and \(F\) as oracles, if the signature passes verification then (by taking \(\log\) to the base of \(g\)) the answers \(x,y\) of these oracles will satisfy \(b\sigma = x + ay\), which means that sufficiently many such equations should be enough to recover the discrete log \(a\).

Before seeing the actual proof, it is a very good exercise to try to see how to convert the intuition above into a formal proof.

Suppose that the discrete logarithm assumption holds for the group \(\mathbb{G}\). Then the DSA signature with \(\mathbb{G}\) is secure when \(H,F\) are modeled as random oracles.

Suppose, for the sake of contradiction, that there was a \(T\)-time adversary \(A\) that succeeds with probability \(\epsilon\) in a chosen message attack against the DSA scheme. We will show that there is an adversary that can compute the discrete logarithm with running time and probability polynomially related to \(T\) and \(\epsilon\) respectively.

Recall that in a chosen message attack in the random oracle model, the adversary interacts with a signature oracle and oracles that compute the functions \(F\) and \(H\). For starters, we consider the following experiment \(\ensuremath{\mathit{CMA}}'\), where in the chosen message attack we replace the signature box with the following “fake signature oracle” and “fake function \(F\) oracle”:

On input a message \(m\), the fake box will choose \(\sigma,r\) at random in \(\{0,\ldots,p-1\}\) (where \(p=|\mathbb{G}|\)), and compute and output \((f,\sigma)\). We will then record the value \(F(f)=r\) and answer \(r\) on future queries to \(F\). If we’ve already answered \(F(f)\) before with a different value, then we halt the experiment and output an error. We claim that the adversary’s chance of succeeding in \(\ensuremath{\mathit{CMA}}'\) is computationally indistinguishable from its chance of succeeding in the original \(\ensuremath{\mathit{CMA}}\) experiment. Indeed, since we choose the value \(r=F(f)\) at random, as long as we don’t repeat a value \(f\) that was queried before, the function \(F\) is completely random. But since the adversary makes at most \(T\) queries, and each \(f\) is chosen according to Equation 9.1, which yields a random element the group \(\mathbb{G}\) (which has size roughly \(2^n\)), the probability that \(f\) is repeated is at most \(T/|\mathbb{G}|\), which is negligible. Now we computed \(\sigma\) in the fake box as a random value, but we can also compute \(\sigma\) as equaling \(b^{-1}(H(m)+a r) \mod p\), where \(b=\log_g f \mod p\) is uniform as well, and so the distribution of the signature \((f,\sigma)\) is identical to the distribution by a real box.

Note that we can simulate the result of the experiment \(\ensuremath{\mathit{CMA}}'\) without access to the value \(a\) such that \(h=g^a\). We now transform an algorithm \(A'\) that manages to forge a signature in the \(\ensuremath{\mathit{CMA}}'\) experiment into an algorithm that given \(\mathbb{G},g,g^a\) manages to recover \(a\).

We let \((m^*,f^*,\sigma^*)\) be the message and signature that the adversary \(A'\) outputs at the end of a successful attack. We can assume without loss of generality that \(f^*\) is queried to the \(F\) oracle at some point during the attack. (For example, by modifying \(A'\) to make this query just before she outputs the final signature.) So, we split into two cases:

Case I: The value \(F(f^*)\) is first queried by the signature box.

Case II: The value \(F(f^*)\) is first queried by the adversary.

If Case I happens with non-negligible probability, then we know that the value \(f^*\) is queried when producing the signature \((f^*,\sigma)\) for some message \(m \neq m^*\), and so we know the following two equations hold:

If Case II happens, then we split it into two cases as well.

Case IIa is the subcase of Case II where \(F(f^*)\) is queried before \(H(m^*)\) is queried, and Case IIb is the subscase of Case II when \(F(f^*)\) is queried after \(H(m^*)\) is queried.

We start by considering the setting that Case IIa happens with non-negligible probability \(\epsilon\). By the averaging argument there are some \(t'< t \in \{1,\ldots,T\}\) such that with probability at least \(\epsilon/T^2\), \(f^*\) is queried by the adversary at the \(t'\)-th query and \(m^*\) is queried by the adversary at its \(t\)-th query. We run the \(\ensuremath{\mathit{CMA}}'\) experiment twice, using the same randomness up until the \(t-1\)-th query and independent randomness from then onwards. With probability at least \((\epsilon/T^2)^2\), both experiments will result in a successful forge, and since \(f^*\) was queried before at stage \(t'<t\), we get the following equations

If Case IIb happens with non-negligible probability, \(\epsilon>0\). Then again by the averaging argument there are some \(t< t' \in \{1,\ldots,T\}\) such that with probability at least \(\epsilon/T^2\), \(m^*\) is queried by the adversary at the \(t\)-th query, and \(f^*\) is queried by the adversary at its \(t'\)-th query. We run the \(\ensuremath{\mathit{CMA}}'\) experiment twice, using the same randomness up until the \(t'-1\)-th query and independent randomness from then onwards. This time we will get the two equations

The bottom line is that we obtain a probabilistic polynomial time algorithm that on input \(\mathbb{G},g,g^a\) recovers \(a\) with non-negligible probability, hence violating the assumption that the discrete log problem is hard for the group \(\mathbb{G}\).

In this lecture both our encryption scheme and digital signature schemes were not proven secure under a well-stated computational assumption but rather used the random oracle model heuristic. However, it is known how to obtain schemes that do not rely on this heuristic, and we will see such schemes later on in this course.

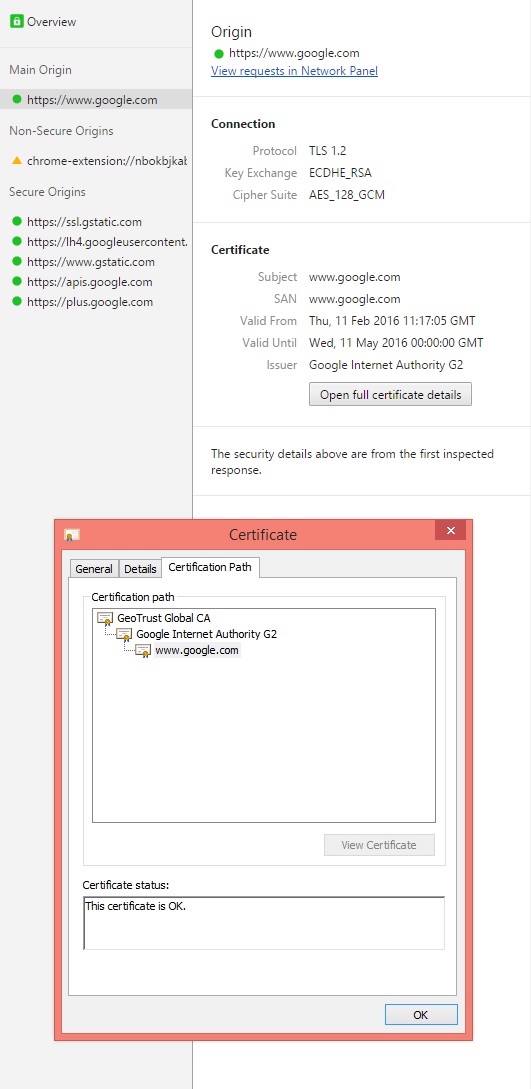

Putting everything together - security in practice.

Let us discuss briefly how public key cryptography is used to secure web traffic through the SSL/TLS protocol that we all use when we use https:// URLs. The security this achieves is quite amazing. No matter what wired or wireless network you are using, no matter what country you are in, as long as your device (e.g., phone/laptop/etc..) and the server you are talking to (e.g., Google, Amazon, Microsoft etc.) is functioning properly, you can communicate securely without any party in the middle able to either learn or modify the contents of your interaction.9

In the web setting, there are servers who have public keys, and users who generally don’t have such keys. Ideally, as a user, you should already know the public keys of all the entities you communicate with e.g., amazon.com, google.com, etc. However, how are you going to learn those public keys? The traditional answer was that because they are public these keys are much easier to communicate and the servers could even post them as ads on the New York Times. Of course these days everyone reads the Times through nytimes.com and so this seems like a chicken-and-egg type of problem.

The solution goes back again to the quote of Archimedes of “Give me a fulcrum, and I shall move the world”. The idea is that trust can be transitive. Suppose you have a Mac. Then you have already trusted Apple with quite a bit of your personal information, and so you might be fine if this Mac came pre-installed with the Apple public key which you trust to be authentic. Now, suppose that you want to communicate with Amazon.com. Now, you might not know the correct public key for Amazon, but Apple surely does. So Apple can supply Amazon with a signed message to the effect of

“I Apple certify that the public key of Amazon.com is

30 82 01 0a 02 82 01 01 00 94 9f 2e fd 07 63 33 53 b1 be e5 d4 21 9d 86 43 70 0e b5 7c 45 bb ab d1 ff 1f b1 48 7b a3 4f be c7 9d 0f 5c 0b f1 dc 13 15 b0 10 e3 e3 b6 21 0b 40 b0 a3 ca af cc bf 69 fb 99 b8 7b 22 32 bc 1b 17 72 5b e5 e5 77 2b bd 65 d0 03 00 10 e7 09 04 e5 f2 f5 36 e3 1b 0a 09 fd 4e 1b 5a 1e d7 da 3c 20 18 93 92 e3 a1 bd 0d 03 7c b6 4f 3a a4 e5 e5 ed 19 97 f1 dc ec 9e 9f 0a 5e 2c ae f1 3a e5 5a d4 ca f6 06 cf 24 37 34 d6 fa c4 4c 7e 0e 12 08 a5 c9 dc cd a0 84 89 35 1b ca c6 9e 3c 65 04 32 36 c7 21 07 f4 55 32 75 62 a6 b3 d6 ba e4 63 dc 01 3a 09 18 f5 c7 49 bc 36 37 52 60 23 c2 10 82 7a 60 ec 9d 21 a6 b4 da 44 d7 52 ac c4 2e 3d fe 89 93 d1 ba 7e dc 25 55 46 50 56 3e e0 f0 8e c3 0a aa 68 70 af ec 90 25 2b 56 f6 fb f7 49 15 60 50 c8 b4 c4 78 7a 6b 97 ec cd 27 2e 88 98 92 db 02 03 01 00 01”

Such a message is known as a certificate, and it allows you to extend your trust in Apple to a trust in Amazon. Now when your browser communicates with Amazon, it can request this message, and if it is not present terminate the interaction or at least display some warning. Clearly a person in the middle can stop this message from travelling and hence not allow the interaction to continue, but they cannot spoof the message and send a certificate for their own public key, unless they know Apple’s secret key. (In today’s actual implementation, for various business and other reasons, the trusted keys that come pre-installed in browsers and devices do not belong to Apple or Microsoft but rather to particular companies such as Verisign known as certificate authorities. The security of these certificate authorities’ private key is crucial to the security of the whole protocol, and it has been attacked before.)

Using certificates, we can assume that Bob the user has the public verification key \(v\) of Alice the server. Now Alice can send Bob also a public encryption key \(e\), which is authenticated by \(v\) and hence guaranteed to be correct.10 Once Bob knows Alice’s public key they are in business- he can use that to send an encryption of some private key \(k\), which they can then use for all the rest of their communication.

This is, at a very high level, the SSL/TLS protocol, but there are many details inside it including the exact security notions needed from the encryption, how the two parties negotiate which cryptographic algorithm to use, and more. All these issues can and have been used for attacks on this protocol. For two recent discussions see this blog post and this website.

Example: Here is the list of certificate authorities that were trusted by default (as of spring 2016) by Mozilla products: Actalis, Amazon, AS Sertifitseerimiskeskuse (SK), Atos, Autoridad de Certificacion Firmaprofesional, Buypass, CA Disig a.s., Camerfirma, Certicámara S.A., Certigna, Certinomis, certSIGN, China Financial Certification Authority (CFCA), China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC), Chunghwa Telecom Corporation, Comodo, ComSign, Consorci Administració Oberta de Catalunya (Consorci AOC, CATCert), Cybertrust Japan / JCSI, D-TRUST, Deutscher Sparkassen Verlag GmbH (S-TRUST, DSV-Gruppe), DigiCert, DocuSign (OpenTrust/Keynectis), e-tugra, EDICOM, Entrust, GlobalSign, GoDaddy, Government of France (ANSSI, DCSSI), Government of Hong Kong (SAR), Hongkong Post, Certizen, Government of Japan, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Government of Spain, Autoritat de Certificación de la Comunitat Valenciana (ACCV), Government of Taiwan, Government Root Certification Authority (GRCA), Government of The Netherlands, PKIoverheid, Government of Turkey, Kamu Sertifikasyon Merkezi (Kamu SM), HARICA, IdenTrust, Izenpe S.A., Microsec e-Szignó CA, NetLock Ltd., PROCERT, QuoVadis, RSA the Security Division of EMC, SECOM Trust Systems Co. Ltd., Start Commercial (StartCom) Ltd., Swisscom (Switzerland) Ltd, SwissSign AG, Symantec / GeoTrust, Symantec / Thawte, Symantec / VeriSign, T-Systems International GmbH (Deutsche Telekom), Taiwan-CA Inc. (TWCA), TeliaSonera, Trend Micro, Trustis, Trustwave, TurkTrust, Unizeto Certum, Visa, Web.com, Wells Fargo Bank N.A., WISeKey, WoSign CA Limited

Appendix: An alternative proof of the density of primes

I record here an alternative way to show that the fraction of primes in \([2^n]\) is \(\Omega(1/n)\).11

The probability that a random \(n\) bit number is prime is at least \(\Omega(1/n)\).

Let \(N=2^n\). We need to show that the number of primes between \(1\) and \(N\) is at least \(\Omega(N/\log N)\). Consider the number \(\binom{2N}{N}=\tfrac{2N!}{N!N!}\). By Stirling’s formula we know that \(\log \binom{2N}{N} = (1 - o(1))2N\) and in particular \(N \leq \log\binom{2N}{N} \leq 2N\). Also, by the formula using factorials, all the prime factors of \(\binom{2N}{N}\) are between \(0\) and \(2N\), and each factor \(P\) cannot appear more than \(k=\floor{\tfrac{\log 2N}{\log P}}\) times. Indeed, for every \(N\), the number of times \(P\) appears in the factorization of \(N!\) is \(\sum_i \floor{\tfrac{N}{P^i}}\), since we get \(\floor{\tfrac{N}{P}}\) times a factor \(P\) in the factorizations of \(\{1,\ldots,N\}\), \(\floor{\tfrac{N}{P^2}}\) times a factor of the form \(P^2\), etc. Thus, the number of times \(P\) appears in the factorization of \(\binom{2N}{N}=\tfrac{(2N)!}{N!N!}\) is equal to \(\sum_i \floor{\tfrac{2N}{P^i}}-2\floor{\tfrac{N}{P^i}}\): a sum of at most \(k\) elements (since \(P^{k+1}>2N\)) each of which is either \(0\) or \(1\).

Thus, \(\binom{2N}{N} \leq \prod_{\substack{1 \leq P \leq 2N \\ P \text{ prime }}} P^{\floor{\tfrac{\log 2N}{\log P}}}\). Taking logs we get that

Additional Group Theory Exercises and Proofs

Below are optional group theory related exercises and proofs meant to help gain an intuition with group theory. Note that in this class, we tend only to talk about finite commutative groups \(\mathbb{G}\), but there are more general groups:

For example, the integers (i.e. infinitely many elements) where the operation is addition is a commutative group: if \(a,b,c\) are integers, then \(a+b = b+a\) (commutativity), \((a+b)+c = a+(b+c)\) (associativity), \(a+0 = a\) (so \(0\) is the identity element here; we typically think of the identity as \(1\), especially when the group operation is multiplication), and \(a+(-a) = 0\) (i.e. for any integer, we are allowed to think of its additive inverse, which is also an integer).

A non-commutative group (or a non-abelian group) is a group such that \(\exists a,b \in \mathbb{G}\) but \(a * b \neq b * a\) (where \(*\) is the group operation). One example (of an infinite, non-commutative group) is the set of \(2 \times 2\) matrices (over the real numbers) which are invertible, and the operation is matrix multiplication. The identity element is the traditional identity matrix, and each matrix has an inverse (and the product of two invertible matrices is still invertible), and matrix multiplication satisfies associativity. However, matrix multiplication here need not satisfy commutativity.

In this class, we restrict ourselves to finite commutative groups to avoid complications with infinite group orders and annoyances with non-commutative operations. For the problems below, assume that a “group” is really a “finite commutative group”.

Here are five more important groups used in cryptography other than \(\mathbb{Z}_{p}\). Recall that groups are given by a set and a binary operation.

- For some prime \(p\), \(\mathbb{Z}_p^{*}=\{1,\ldots , p-1\}\), with operation multiplication mod \(p\) (Note: the \(^{*}\) is to distinguish this group from \(\mathbb{Z}_p\) with an additive operation and from \(\ensuremath{\mathit{GF}}(p)\).)

- The quadratic residues of \(\mathbb{Z}_p^{*}\): \(Q_p=\{a^2:a\in \mathbb{Z}_p^{*}\}\) with operation multiplication mod \(p\)

- \(\mathbb{Z}_n^{*}\), where \(n=p\cdot q\) (product of two primes)

- The quadratic residues of \(\mathbb{Z}_n^{*}\):: \(Q_n=\{a^2:a\in \mathbb{Z}_n^{*}\}\), where \(n=p\cdot q\)

- Elliptic curve groups

For more familiarity with group definitions, you could verify that the first 4 groups satisfy the group axioms. For cryptography, two operations need be efficient for elements \(a,b\) in group \(\mathbb{G}\):

- Exponentiation: \(a,b\mapsto a^b\). This is done efficiently using repeated squaring, i.e. generate all the squares up to \(2^k\) and then use the binary representation.

- Inverse: \(a \mapsto a^{-1}\). This is done efficiently in \(\mathbb{Z}_p^{\*}\) by Fermat’s little theorem. \(a^{-1}=a^{p-2}\) mod \(p\).

Solved exercises:

Is the set \(S = \{1,2,3,4,5,6\}\) a group if the operation is multiplication mod \(7\)? What if the operation is addition mod \(7\)?

Yes (if multiplication) and no (if addition). To prove that something is a group, we run through the definition of a group. This set is finite, and multiplication (even multiplication mod some number) will satisfy commutativity and associativity. The identity element is \(1\) because any number times \(1\), even mod \(7\), is still itself. To find inverses, we can in this case literally find the inverses. \(1 * 1 \mod 7 = 1 \mod 7\) (so the inverse of \(1\) is \(1\)). \(2 * 4 \mod 7 = 8 \mod 7 = 1 \mod 7\) (so the inverse of \(2\) is \(4\), and from commutativity, the inverse of \(4\) is \(2\)). \(3 * 5 \mod 7 = 15 \mod 7 = 1 \mod 7\) (so the inverse of \(3\) is \(5\), and the inverse of \(5\) is \(3\)). \(6 * 6 \mod 7 = 36 \mod 7 = 1 \mod 7\) (so \(6\) is its own inverse; notice that an element can be its own inverse, even if it is not the identity \(1\)). The set \(S\) is not a group if the operation is addition for many reasons: one way to see this \(1+6 \mod 7 = 0 \mod 7\), but \(0\) is not an element of \(S\), so this group is not closed under its operation (implicit in the definition of a group is the idea that a group’s operation must send two group elements to another element within the same set of group elements).

What are the generators of the group \(\{1,2,3,4,5,6 \}\), where the operation is multiplication mod \(7\)?

\(3\) and \(5\). Recall that a generator of a group is an element \(g\) such that \(\{g,g^2,g^3,\cdots\}\) is the entire group. We can directly check the elements here: \(\{1,1^2,1^3,\cdots\} = \{1\}\), so \(1\) is not a generator. \(2\) is not a generator because \(2^3 \mod 7 = 8 \mod 7 = 1\), so the set \(\{2,2^2,2^3,2^4,\cdots\}\) is really the set \(\{2,4,1\}\), which is not the entire group. \(3\) will be a generator because \(3^2 \mod 7 = 9 \mod 7 = 2 \mod 7\), \(3^3 \mod 7 = 2*3 \mod 7 = 6 \mod 7\), \(3^3 \mod 7 = 18 \mod 7 = 4 \mod 7\), \(3^4 = 12 \mod 7 = 5\), \(3^5 \mod 7 = 15 \mod 7 = 1\), so \(\{3,3^2,3^3,3^4,3^5,3^6,3^7 \} = \{3,2,6,4,5,1\}\), which are all of the elements. \(4\) is not a generator because \(4^3 \mod 7 = 64 \mod 7 = 1 \mod 7\), so just like \(2\), we won’t get every element. \(5\) is a generator because \(5^2 \mod 6 = 4, 5^3 \mod 7 = 20 \mod 7 = 6, 5^4 \mod 7 = 30 \mod 7 = 2, 5^5 \mod 7 = 10 \mod 7 = 3, 5^6 \mod 7 = 15 \mod 7 = 1\), so just like \(3\), \(5\) is a generator. \(6\) is not a generator because \(6^2 \mod 7= 1 \mod 7\), so just like \(2\), the set \(\{6,6^2,6^3,\cdots\}\) cannot contain all elements (it will just have \(1\) and \(6\)).

What is the order of every element in the group \(\{1,2,3,4,5,6 \}\), where the operation is multiplication mod \(7\)?

The orders (of \(1,2,3,4,5,6\)) are \(1,3, 6, 3, 6, 2\), respectively. This can be seen from the work of the previous problem, where we test out powers of elements. Notice that all of these orders divide the number of elements in our group. This is not a coincidence, and it is an example of Lagrange’s Theorem, which states that the size of every subgroup of a group will divide the order of a group. Recall that a subgroup is simply a subset of the group which is a group in its own right and is closed under the operation of the group.

Suppose we have some (finite, commutative) group \(\mathbb{G}\). Prove that the inverse of any element is unique (i.e. prove that if \(a \in \mathbb{G}\), then if \(b,c \in \mathbb{G}\) such that \(ab = 1\) and \(ac = 1\), then \(b=c\)).

Suppose that \(a \in \mathbb{G}\) and that \(b,c \in \mathbb{G}\) such that \(ab = 1\) and \(ac = 1\). Then we know that \(ab = ac\), and then we can apply \(a^{-1}\) to both sides (we are guaranteed that \(a\) has SOME inverse \(a^{-1}\) in the group), and so we have \(a^{-1}ab = a^{-1}ac\), but we know that \(a^{-1}a = 1\) (and we can use associativity of a group), so \((1)b = (1)c\) so \(b = c\). QED.

Suppose we have some (finite, commutative) group \(\mathbb{G}\). Prove that the identity element is unique (i.e. if \(ca = c\) for all \(c \in \mathbb{G}\) and if \(cb = c\) for all \(c \in \mathbb{G}\), then \(a=b\)).

Suppose that \(ca = c\) for all \(c \in \mathbb{G}\) and that \(cb = c\) for all \(c \in \mathbb{G}\). Then we can say that \(ca =c = cb\) (for any \(c\), but we can choose some \(c\) in particular, we could have picked \(c=1\)). And then \(c\) has some inverse element \(c^{-1}\) in the group, so \(c^{-1}ca = c^{-1}cb\), but \(c^{-1}c = 1\), so \(a = b\) as desired. QED

The next few problems are related to quadratic residues, but these problems are a bit more general (in particular, we are considering some group, and a subgroup which are all of the elements of the first group which are squares).

Suppose that \(\mathbb{G}\) is some (finite, commutative) group, and \(\mathbb{H}\) is the set defined by \(\mathbb{H} := \{ h \in \mathbb{G}: \exists g \in G, g^2 = h\}\). Verify that \(\mathbb{H}\) is a subgroup of \(\mathbb{G}\).

To be a subgroup, we need to make sure that \(\mathbb{H}\) is a group in its own right (in particular, that it contains the identity, that it contains inverses, and that it is closed under multiplication; associativity and commutativity follow because we are within a larger set \(\mathbb{G}\) which satisfies associativity and commutativity).

Identity Well, \(1^2 = 1\), so \(1 \in \mathbb{H}\), so \(\mathbb{H}\) has the identity element. Inverses If \(h \in \mathbb{H}\), then \(g^2 = h\) for some \(g \in \mathbb{G}\), but \(g\) has an inverse in \(\mathbb{G}\), and we can look at \(g^2(g^{-1})^2 = (gg^{-1})^2 = 1^2 = 1\) (where I used commutativity and associativity, as well as the definition of the inverse). It is clear that \((g^{-1})^2 \in \mathbb{H}\) because there exists an element in \(\mathbb{G}\) (specifically, \(g^{-1}\)) whose square is \((g^{-1})^2\). Therefore \(h\) has an inverse in \(\mathbb{H}\), where if \(h=g^2\), then \(h^{-1} = (g^{-1})^2\). Closure under operation If \(h_1,h_2 \in \mathbb{H}\), then there exist \(g_1,g_2 \in \mathbb{G}\) where \(h_1 = (g_1)^2, h_2 = (g_2)^2\). So \(h_1h_2 = (g_1)^2(g_2)^2 = (g_1g_2)^2\), so \(h_1h_2 \in \mathbb{H}\). Therefore, \(\mathbb{H}\) is a subgroup of \(\mathbb{G}\).

Assume that \(|\mathbb{G}|\) is an even number and is known, and that \(g^{|\mathbb{G}|}=1\) for any \(g \in \mathbb{G}\). Also assume that \(\mathbb{G}\) is a cyclic group, i.e. there is some \(g \in \mathbb{G}\) such that any element \(f \in \mathbb{G}\) can be written as \(f^k\) for some integer \(k\). Also assume that exponentiation is efficient in this context (i.e. we can compute \(g^r\) for any \(0 \leq r \leq |\mathbb{G}|\) in an efficient time for any \(g \in \mathbb{G}\)).

Under the assumptions stated above, prove that there is an efficient way to check if some element of \(\mathbb{G}\) is also an element of \(\mathbb{H}\), where \(\mathbb{H}\) is still the subgroup of squares of elements of \(\mathbb{G}\) (note: running through all possible elements of \(\mathbb{G}\) may not be efficient, so this cannot be your strategy).

Suppose that we receive some element \(g \in \mathbb{G}\). We want to know if there exists some \(g' \in \mathbb{G}\) such that \(g = (g')^2\) (this is equivalent to \(g\) being in \(\mathbb{H}\)). To do so, compute \(g^{|\mathbb{G}|/2}\). I claim that \(g^{|\mathbb{G}|/2}=1\) if and only if \(g \in \mathbb{H}\).

(Proving the if): If \(g \in \mathbb{H}\), then \(g=(g')^2\) for some \(g' \in \mathbb{G}\). We then have that \(g^{|\mathbb{G}|/2} = ((g')^2)^{|\mathbb{G}|/2} = (g')^{|\mathbb{G}|}\). But from our assumption, an element raised to the order of the group is \(1\), so \((g')^{|\mathbb{G}|} = 1\), so \(g^{|\mathbb{G}|/2} = 1\). As a result, if \(g \in \mathbb{H}\), then \(g^{|\mathbb{G}|/2} = 1\).

(Proving the only if): Now suppose that \(g^{|\mathbb{G}|/2} = 1\). At this point, we use the fact that \(\mathbb{G}\) is cyclic, so let \(f \in \mathbb{G}\) be the generator of \(\mathbb{G}\). We know that \(g\) is some power of \(f\), and this power is either even or odd. If the power is even, we are done. If the power is odd, then \(g = f^{2k+1}\) for some natural number \(k\). And then we see \(g^{|\mathbb{G}|/2} = (f^{2k+1})^{|\mathbb{G}|/2} = f^{|\mathbb{G}| + |\mathbb{G}|/2} = f^{|\mathbb{G}|}f^{|\mathbb{G}|/2}\). We can use the assumption that any element raised to its group’s order is \(1\), so \(1 = g^{|\mathbb{G}|/2} = f^{|\mathbb{G}|}f^{|\mathbb{G}|/2} = f^{|\mathbb{G}|/2}\). This tells us that the order of \(f\) is at most \(|\mathbb{G}|/2\), but this is a contradiction because \(f\) is a generator of \(\mathbb{G}\), so its order cannot be less than \(|\mathbb{G}|\) (if it were, then looking at \(\{f,f^2,f^3,\cdots\}\), we would only count at most half of the elements before cycling back to \(1,f,f^2,\cdots\), so this set wouldn’t contain all of \(\mathbb{G}\)). As a result, we have reached a contradiction, so \(g^{|\mathbb{G}|/2} = 1\) means that \(g = f^{2k} = (f^k)^2\), so \(g \in \mathbb{H}\).

We are given that this exponentiation is efficient, so checking \(g^{|\mathbb{G}|/2} == 1\) is an efficient and correct way to test if \(g \in \mathbb{H}\). QED.

This proof idea came from here as well as from the 2/25/20 lecture at Harvard given by MIT professor Yael Kalai.

Commentary on assumptions and proof: Proving that \(g^{|\mathbb{G}|}=1\) is a useful exercise in its own right, but it overlaps somewhat with our problem sets of 2020, so we will not prove it here; observe that if \(\mathbb{G}\) is the set of \(\{1,2,3,\cdots,p-1\}\) for some prime \(p\), then this is a special case of Fermat’s Little Theorem, which states that \(a^{p-1} \mod p = 1\) for \(a \in \{1,2,3,\cdots,p-1\}\). Also, one can prove that \(Z_p^{\*}\) (the set of numbers \(0,1,2,\cdots,p-1\), with operation multiplication mod \(p\)) for \(p\) a prime is cyclic, where one method can be found here, where the proof comes down to factorizing certain polynomials and decomposing numbers in terms of prime powers. We can then see that this proof above says that there is an efficient way to test whether an element of \(Z_p^{\*}\) is a square or not.

- ↩

For simplicity, assume that the program \(P\) is side effect free and hence it simply computes some function, say from \(\{0,1\}^n\) to \(\{0,1\}^\ell\) for some \(n,\ell\).

- ↩

There have been some other more exotic suggestions for public key encryption (including some by yours truly as well as suggestions such as the isogeny star problem, though see also this), but they have not yet received wide scrutiny.

- ↩

The running time of the best known algorithms for computing the discrete logarithm modulo \(n\) bit primes is \(2^{f(n)2^{n^{1/3}}}\), where \(f(n)\) is a function that depends polylogarithmically on \(n\). If \(f(n)\) would equal \(1\), then we’d need numbers of \(128^3 \approx 2\cdot 10^6\) bits to get \(128\) bits of security, but because \(f(n)\) is larger than one, the current estimates are that we need to let \(n=3072\) bit key to get \(128\) bits of of security. Still, the existence of such a non-trivial algorithm means that we need much larger keys than those used for private key systems to get the same level of security. In particular, to double the estimated security to \(256\) bits, NIST recommends that we multiply the RSA keysize five-fold to \(15,360\). (The same document also says that SHA-256 gives \(256\) bits of security as a pseudorandom generator but only \(128\) bits when used to hash documents for digital signatures; can you see why?)

- ↩

Formally, the secret key should contain all the information in the public key plus the extra secret information, but we omit the public information for simplicity of notation.

- ↩

Formally, since it is an asymptotic statement, the CDH assumption needs to be defined with a sequence of groups. However, to make notation simpler we will ignore this issue, and use it only for groups (such as the numbers modulo some \(n\) bit primes) where we can easily increase the “security parameter” \(n\).

- ↩

ElGamal’s actual contribution was to design a signature scheme based on the Diffie-Hellman problem, a variant of which is the Digital Signature Algorithm (DSA) described below.

- ↩

For every \(f\in \mathbb{G}\), you can show a one to one and onto mapping between the set \(\{ a : g^a = 1 \}\) and the set \(\{b : g^b= f \}\) by choosing some element \(b\) from the latter set and looking at the map \(a \mapsto a+b \mod |\mathbb{G}|\).

- ↩

It is a bit cumbersome, but not so hard, to transform functions that map strings to strings to functions whose domain or range are group elements. As noted in the KL book, in the actual DSA protocol \(F\) is not a cryptographic hash function but rather some very simple function that is still assumed to be “good enough” for security.

- ↩

They are able to know that such an interaction took place and the amount of bits exchanged. Preventing these kind of attacks is more subtle and approaches for solutions are known as steganography and anonymous routing.

- ↩

If this key is ephemeral- generated on the spot for this interaction and deleted afterward- then this has the benefit of ensuring the forward secrecy property that even if some entity that is in the habit of recording all communication later finds out Alice’s private verification key, then it still will not be able to decrypt the information. In applied crypto circles this property is somewhat misnamed as “perfect forward secrecy” and associated with the Diffie-Hellman key exchange (or its elliptic curves variants), since in those protocols there is not much additional overhead for implementing it (see this blog post). The importance of forward security was emphasized by the discovery of the Heartbleed vulnerability (see this paper) that allowed via a buffer-overflow attack in OpenSSL to learn the private key of the server.

- ↩

It might be that the two ways are more or less the same, as if we open up the polynomial \((1-x)^kx^k\) we get the binomial coefficients.

Comments

Comments are posted on the GitHub repository using the utteranc.es app. A GitHub login is required to comment. If you don't want to authorize the app to post on your behalf, you can also comment directly on the GitHub issue for this page.

Compiled on 11/17/2021 22:36:13

Copyright 2021, Boaz Barak.

This work is

licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Produced using pandoc and panflute with templates derived from gitbook and bookdown.